The Prison Rape Elimination Act Isn’t About Sex. It’s About Power And Accountability

Most people don’t know what the Prison Rape Elimination Act is.

If they’ve heard of it at all, it’s likely through headlines framing it as an “LGBTQ prison policy” now being rolled back by the Trump administration. That framing is dangerously incomplete — and it allows something far more consequential to happen quietly.

The Prison Rape Elimination Act, known as PREA, is not just about sex. It is not just about LGBTQ+ people. It is one of the only federal frameworks that makes a simple but radical demand of prisons, jails, youth detention centers, and other institutions of confinement:

If the state takes custody of a human being, it is responsible for their safety, dignity, and bodily integrity.

As PREA’s enforcement infrastructure is hollowed out — audits defunded, data erased, protections narrowed — the people most at risk are not abstractions. They are Black boys in jails. Disabled men in county lockups. Women coerced by guards. Youth whose “protection” becomes solitary confinement.

I write this not only as a journalist and policy advocate, but as someone whose life has been shaped by these systems from the inside.

What PREA Actually Is

PREA was passed unanimously by Congress in 2003 and signed into law by President George W. Bush. It was one of the rare moments of bipartisan agreement in modern criminal justice policy, declaring sexual abuse in confinement a national crisis and a violation of basic constitutional rights.

The law does three essential things.

First, it establishes national standards requiring facilities to prevent, detect, and respond to sexual abuse and harassment. These standards govern intake screening, housing decisions, use of force, medical and mental health care after assaults, staff training, investigations, and protections against retaliation.

Second, it mandates federal data collection. The Bureau of Justice Statistics conducts ongoing surveys of sexual victimization in prisons, jails, juvenile facilities, and other institutions. This remains the only national data system that documents abuse behind bars, including staff-on-incarcerated-person violence.

Third, PREA requires independent audits and ties compliance to federal funding. States that refuse to certify compliance risk losing millions of dollars in Justice Department grants.

PREA applies not only to prisons, but to jails, youth detention facilities, lockups, and other places where people are confined by the state.

Importantly, PREA does not create a special right to sue. Instead, it creates standards, documentation, and oversight — the raw material that allows incarcerated people, families, advocates, and lawyers to hold institutions accountable in court and in the public eye.

PREA Is Not About Sex; It Is About Power

PREA is often misunderstood because its title focuses on rape. But the law addresses something broader and more uncomfortable: the abuse of power inside systems designed to exert total control over human beings.

Once incarcerated, a person loses the ability to walk away from danger. The state controls their housing, movement, access to medical care, and ability to report harm. PREA intervenes at that point of absolute imbalance and insists that abuse — sexual, physical, or psychological — is not an acceptable condition of punishment.

This is why PREA matters in cases that have nothing to do with sex.

In Rankin County, Mississippi, an investigative report revealed that jail guards strapped an intellectually disabled Black man, Larry Buckhalter, into an electric restraint vest. They shocked him repeatedly, mocked him, filmed the abuse, and circulated the videos among staff.

This was not sexual assault. It was humiliation, torture, and domination — inflicted because the system believed his body did not matter.

PREA was designed to prevent exactly this kind of violence. It requires heightened protections for vulnerable people, limits on the use of force, mandatory medical and mental health evaluations after harm, and investigations that cannot be buried behind job titles or internal silence.

Without PREA, families like Buckhalter’s have almost no leverage. Jails hide behind qualified immunity, opaque grievance systems, and internal reviews that rarely result in accountability. PREA is one of the only frameworks that says plainly: this conduct violates national standards, and the institution must answer for it.

The Racial Reality Behind the Law

For Black communities, PREA sits inside a much longer history.

On paper, the law is race-neutral. In practice, it operates within mass incarceration, which functions as the crude, unevolved descendant of slavery. Black people are disproportionately incarcerated in every system PREA governs. Black boys, Black men with disabilities, and Black women are routinely treated as expendable once confined.

Even the political urgency around prison rape was racialized. Early narratives focused on white victims and Black perpetrators, while decades of violence against Black youth under drug laws went largely ignored. PREA emerged when white communities began to see their own sons inside cages, not when Black communities were already losing generations.

That history matters. But so does the present reality: PREA has become one of the only tools available to interrupt racialized violence inside institutions, even when imperfectly applied.

When “Protection” Becomes Punishment

PREA was meant to reduce harm. But in under-resourced, overcrowded systems, it has often been weaponized.

Facilities identify people as “vulnerable” — youth, LGBTQ+ people, disabled individuals — and instead of building safer housing, they isolate them. Solitary confinement becomes the default response to risk.

I know this firsthand.

I entered the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services at eighteen and left at twenty-seven. While incarcerated, I was raped by a corrections officer. Later, under PREA’s language of “safety,” I was placed in administrative confinement — solitary — for eighteen months. Six of those months were spent on death row due to overcrowding, despite not having a death sentence.

In solitary, I turned twenty-two and twenty-three. I legally changed my name. I watched the world move forward on a small television while learning to shower once a week and sing in a whisper just to survive the silence.

PREA did not save me. But it gave outside advocates a standard to point to. It gave the ACLU language to challenge my confinement. After one visit from an attorney and one letter, my cell door opened.

I was released back into general population as if nothing had happened.

This is PREA’s paradox: it can be used to justify isolation instead of safety — but without it, there is often nothing at all.

Youth, Solitary, and the Cost to Black Boys

The most devastating example of this failure is the treatment of youth.

PREA explicitly discourages solitary confinement for young people and requires alternative housing, mental health care, and continual review. Yet in jails like Rikers Island, Black boys deemed “unsafe” have been routinely isolated instead.

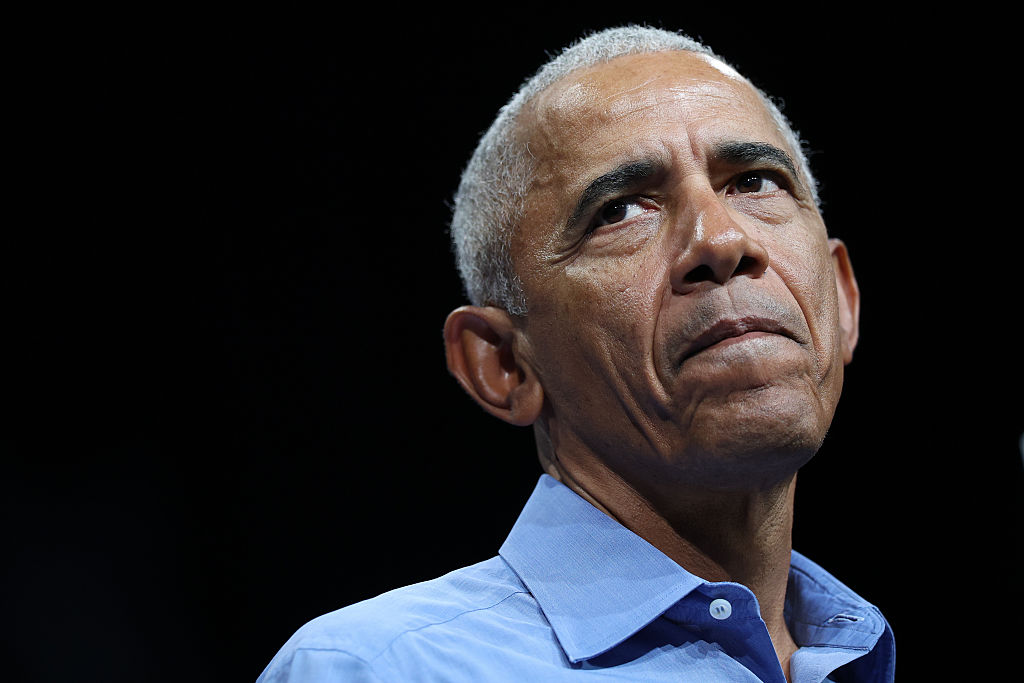

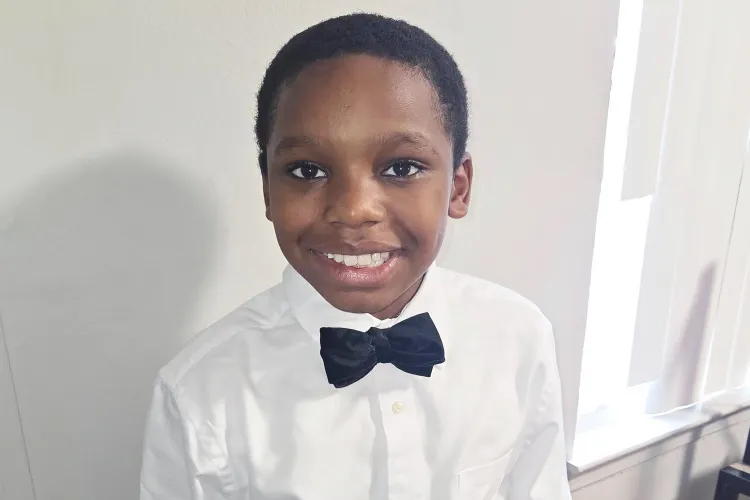

Kalief Browder was 16 when he entered Rikers. Held without trial for nearly three years, he spent extensive time in solitary confinement — often justified as necessary for safety. His mental health deteriorated. After his release, he died by suicide.

Kalief’s story is not an anomaly. It is the predictable outcome of systems that label youth as vulnerable but refuse to invest in safety, treatment, or care.

Why the Current Rollbacks Matter

Today, the Trump administration is dismantling PREA not by repealing the law, but by hollowing it out.

The Department of Justice has defunded the National PREA Resource Center, effectively shutting down the national audit infrastructure. Auditors have been instructed to stop enforcing protections for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. Gender identity questions have been removed from federal crime and prison safety surveys.

This weakens PREA for everyone.

Without audits, abuse goes undocumented. Without data, patterns disappear. Without enforceable standards, institutions revert to secrecy and force.

And when that happens, it is Black bodies — disabled bodies, young bodies, women’s bodies — that absorb the harm.

The Bottom Line

PREA is not a solution to mass incarceration. It does not undo the violence of a system built on punishment and control. But it is one of the only federal tools that insists incarcerated people are still human beings — entitled to safety, medical care, mental health care, and accountability when harmed.

If we allow the Prison Rape Elimination Act to be reduced to a culture-war talking point, we will miss what is actually being taken from us. PREA is one of the few tools that has ever forced prisons and jails to answer for the harm they cause — not just to LGBTQ+ people, but to Black boys, Black women, disabled people, and anyone the state cages and forgets.

We do not have to agree on incarceration to agree on this: no system should be allowed to brutalize human beings in our name without oversight, data, or accountability. Black communities have always understood what happens when violence is hidden behind procedure and paperwork.

Silence has never protected us — it has protected institutions.

Understanding what PREA really is and refusing to let it disappear quietly are one way we interrupt that pattern and insist that the people locked behind concrete walls are still people whose lives matter.

SEE ALSO:

Dominique Morgan, Peachie Wimbush-Polk On Trans Day Of Remembrance

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0