The broader context behind Jacob Robinson’s death: Pedestrian safety gaps in Black communities

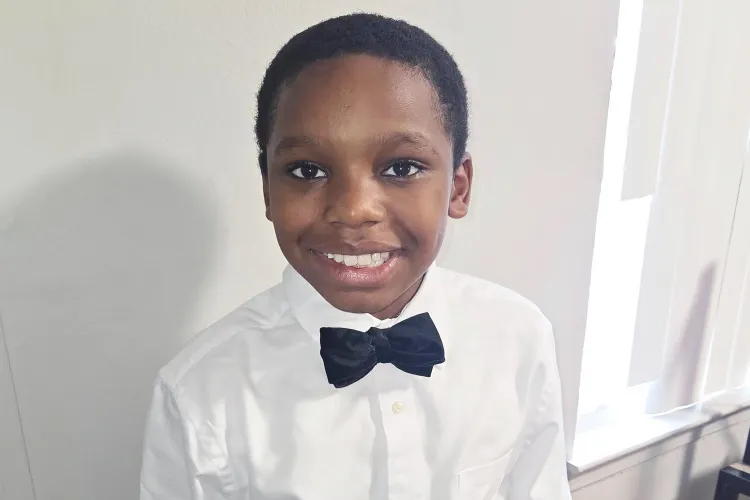

The 11-year-old’s death in Michigan is part of a broader pattern that disproportionately impacts Black children and families.

When Jacob Robinson left home to grab snacks before dark, it was the kind of small freedom many kids cherish. A short walk. A quick errand. A moment of independence.

For too many Black families, even that can carry risk.

Robinson, 11, was fatally struck by a vehicle Tuesday evening near Pond Village Drive and Eureka Road in Taylor, Michigan, according to the police report. Officers responded around 6:37 p.m., administered life-saving measures and transported him to a local hospital, where he later died from his injuries. Police say alcohol and narcotics are not suspected factors, and the driver remained at the scene. The crash remains under investigation.

Jacob’s mother, Tonoya Robinson, said her son had left home on foot to buy snacks. She reminded him to hurry back before it got dark. When her calls went unanswered and she heard ambulance sirens, she said she knew something was wrong.

Jacob was a sixth grader in the Ecorse Public Schools district, which confirmed his death and announced grief counseling for students and staff.

But beyond the heartbreaking details of one family’s loss is a larger, uncomfortable truth: pedestrian deaths have risen sharply in recent years, and Black children are disproportionately affected.

According to national traffic safety data, Black pedestrians are killed at higher rates than their white counterparts. Experts point to a mix of structural factors, including neighborhood infrastructure, limited crosswalk access, poor lighting, higher-speed roadways cutting through residential areas and decades of disinvestment in predominantly Black communities. Many Black neighborhoods are also more “walk-dependent,” meaning residents are more likely to travel on foot for errands, school and daily needs.

In other words, what happened to Jacob is not just about one street corner. It is about design. It is about policy. It is about which communities receive traffic calming measures and which receive four-lane roads running through them.

There is also the emotional layer that Black parents know too well. The talk about the police. The talk about strangers. The talk about staying visible, staying safe, staying alert. What is less discussed is the everyday vulnerability of simply walking while Black in spaces that were not designed with your safety in mind.

For many Black families, independence is complicated by reality. Letting your child walk to the store can feel like a rite of passage. It can also feel like a gamble.

As Jacob’s school community mourns and a GoFundMe circulates to support funeral costs, his story sits at the intersection of private grief and public responsibility. His death underscores a question communities across the country are asking: who gets safe streets?

For Tonoya Robinson, the memory that lingers is the sound of sirens. For the broader Black community, it may also be a renewed call to examine why so many tragedies like this happen on roads that cut through neighborhoods where children live, walk and grow up.

Jacob’s walk to get snacks should have been routine. Instead, it has become a reminder that for Black families, even the most ordinary moments can carry extraordinary weight.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0