Sundance, where greatness begins

Park City, it’s been a ride. Truly. My personal history with the Sundance Film Festival goes back 11 years, when I landed in Utah in 2015, having no idea what to expect.

Sure, I knew there would be films and interviews and events and … snow. But I wasn’t prepared for the education I received. And the connections I made. And importantly — and this is important — I wasn’t prepared to witness the origins of greatness.

But I should have been. Because it’s always been there. In many ways, just as the event’s founder, the late Robert Redford, envisioned.

There have been many incredible creators who have gone on to shape art and present it to the masses in the most life-changing ways. Some became the architects of what the current cinematic landscape is.

But Sundance is where Reggie Hudlin premiered House Party in 1990. At its core, it’s a film about safe sex, but wrapped in a music-filled, good old, no-parents-invited weekday party that defined what it meant to be a teen in the 1990s.

It’s the place where Gina Prince-Bythewood fine-tuned her breakout feature debut Love and Basketball in workshops, before ultimately premiering it at the festival in 2000. The film expanded what we’ve come to expect from female-led films, the landscape of Black stories and the advancement of women’s sports.

Sundance is where we all were introduced to director Chinonye Chukwu via her incredibly researched and performed film Clemency, in which Aldis Hodge expertly puts a face on death row inmates, and Alfre Woodard gives humanity to the people who carry out executions.

And of course, Sundance helped to amplify Ryan Coogler’s voice. We don’t get to a groundbreaking 16 Academy Award nominations for his film Sinners without the work he put in developing Fruitvale Station in a Sundance workshop. The Michael B. Jordan-led project later premiered there in 2014.

Filmmaker Deon Taylor brought his first project, Supremacy, to Sundance in 2014. It wasn’t selected for the festival, Taylor surmised, largely because the film was in a similar thematic vein as Coogler’s breakout indie project.

“They felt like it was a little bit too politically on the same scope,” Taylor told me. “I sat at Ryan’s screening and watched Fruitvale. Wow. I just remember the emotion everybody had when they watched that film. I remember just being blessed to be there. It was so good. But it was a moment for me to first see how film festivals work.”

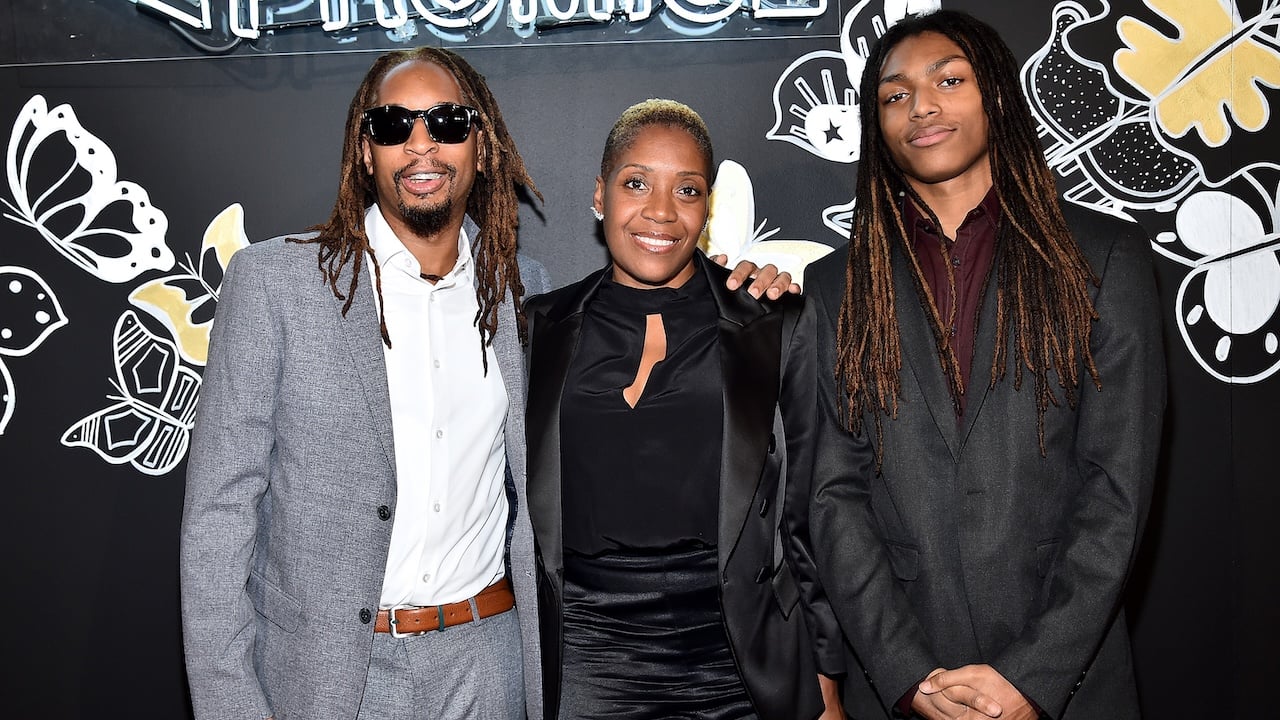

And he did. Together with his wife Roxanne, the Taylors have become quite the force in Hollywood.

For years, Hidden Empire Film Group has largely produced Black-led films and has done quite well. Their independent films have grossed more than $300 million worldwide.

Lily Lawrence/Getty Images

For many years, people such Brickson Diamond helped create space at festivals like Sundance for Black art through his group Blackhouse, a foundation that helps expand opportunities for Black content creators in film, television, digital and emerging platforms.

Blackhouse was born nearly 20 years ago after Diamond attended his first Sundance festival and screened Hustle & Flow – again, an incredibly Black story that found an audience at what was then a stridently white festival. Inspiration struck and over the years, he brought a record amount of Black films, moderated panels, and events to the festival.

For years before Blackhouse set up shop during the festival, you could be Black and go to Sundance.

But what happened once you got there?

“You have to remember myself and Roxanne, we have no clue coming into Hollywood how any of this works,” Taylor said. “I’m thinking to myself, ‘I love movies. I’m going to make a movie.’ Never in a million years did I think, ‘Oh, you can meet people and there are these things called film festivals.’ We had no communication with anyone in the film world.

‘So when I came here, Blackhouse allowed me to be here. They did a whole presentation. We screened a movie. We did a whole Q&A, and they allowed me to feel like I was a part of Sundance, an extension of it.”

Taylor’s company derives from the sports world. While playing basketball overseas, he’d ask loved ones to send him DVDs so he could stay updated on American entertainment. Inspiration struck and Taylor decided to become a filmmaker, leaning on his family and friends who were athletes to invest in his company.

Years later, Taylor’s risky move paid off. The company recently spun off and created Hidden Empire Sports Collective, which is doing groundbreaking things in Hollywood. This new group makes the argument that athletes are no longer simply the subject of art; they’re the actual storytellers. So in addition to telling sports-themed narratives, the Taylors are teaching athletes who want to become cinematographers, writers, directors and more.

In addition to the collective providing hands-on training for athletes to become directors, producers, and writers, they’re also focused on creating sports-driven intellectual property – both documentaries and scripted series – and they’re working with the NFL to host workshops in their Santa Monica, California, offices.

“We have always been the underdog and we had to create something out of nothing,” Roxanne Taylor said. “And this is what this festival actually represents — they support the underdogs. It’s in all of their messaging about giving people opportunities they would not have had. I think the reason why we’ve been so blessed and so successful is because our stories identify with everyone.

“Everyone can relate to every character in our films. And whether it’s action or thriller or comedy, there is a real human story that lies underneath that. And we’re just authentic people because that’s where we come from.”

So many films that I saw at that first Sundance were jarring. They were films that dove deep into the painful parts of the Black experience, and I consumed them with a largely white audience. The irony was rich: Black art being accepted, celebrated and launched at a stridently non-Black film festival.

The films I screened that first year spoke directly to the struggles that our parents and grandparents fought so hard to live through and overcome. They were the stories that we talked about at our dinner tables; they’re the American stories that educate the collective once they hit a 50-foot screen. That year, we saw homage paid to the late Nina Simone through a documentary that chronicled her heartbreaking story of civil rights battles.

I also watched an incredible film on the Black Panther Party through the lens of Stanley Nelson. And I watched the gut-wrenching story of a Florida teen – in the aftermath of Trayvon Martin’s death – senselessly and fatally shot by a white man at a gas station for playing his music “too loudly,” according to his killer.

The stories were gripping. And that they were first seen at Sundance was incredible.

And while the festival isn’t ending, it’s changing locations. Park City was a magical space for Sundance to be born, but it has simply outgrown the scenic Main Street that it’s lived on since 1981. The energy in this year’s festival felt different — Redford, who passed away last year, was rightly mourned, but so much of what we were accustomed to seeing and who we were accustomed to seeing were missing. There was no Blackhouse this year. And the African American Film Critics Association, which has been hosting events and panels there these past few years, was also not in attendance.

Still, there was a noticeable amount of Black creatives in Park City this year – behind-the-scenes artisans who might very well be among our most celebrated and talked about in the next few years.

And really, to me, that’s what Sundance gets right. Yes, it’s the festival that launches the films we’ll be talking about during awards season. But it’s also the place where attendees get to discover talent – both in front of and most certainly behind the camera.

Goodbye, Park City. You were a fabulous host for so many incredible and cinematic moments. Boulder, Colorado: You’ve got a legendary first act to follow.

The post Sundance, where greatness begins appeared first on Andscape.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0