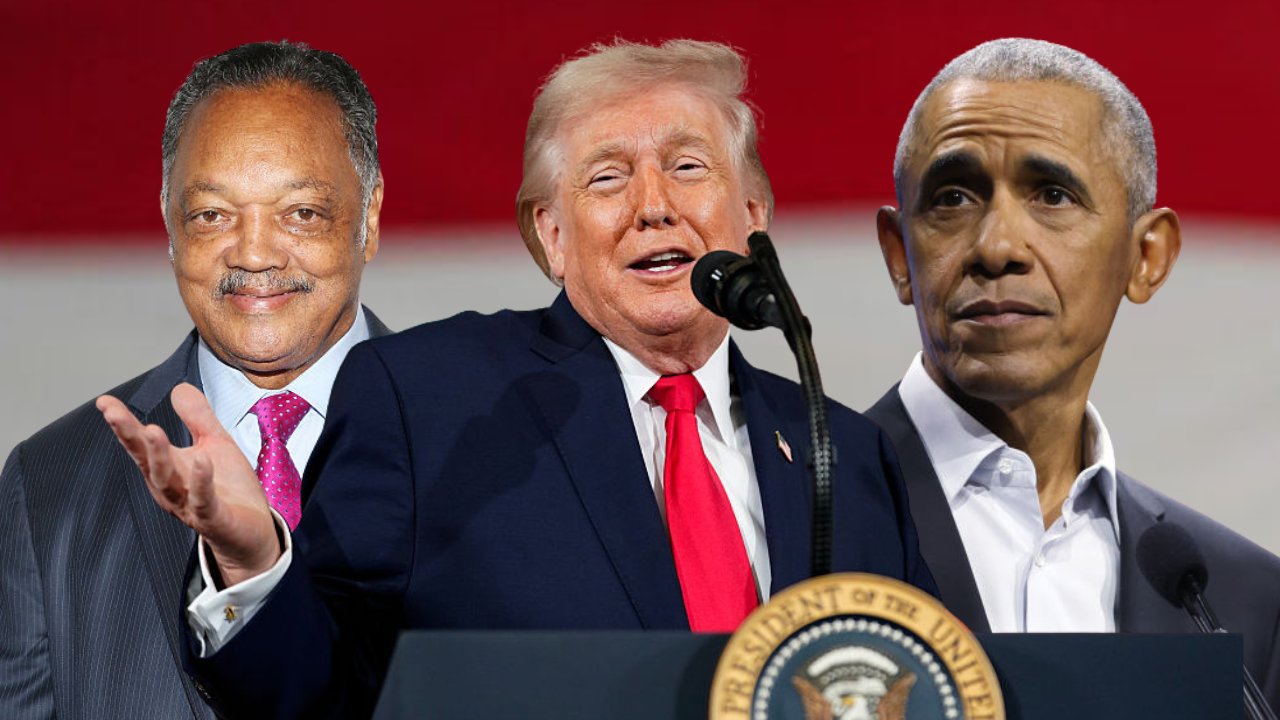

What did Jesse Jackson want? ‘To take common sense to high places.’

What does Jesse want?

The question followed Jesse Louis Jackson through much of his remarkable life. He experienced many incarnations through six decades in the national spotlight — fiery preacher, respected civil rights leader, self-appointed corporate interlocutor, unlikely hostage negotiator, pioneering presidential candidate, “shadow” senator, political adviser, international peacemaker, all-purpose activist.

Long before the United States had an actual Black president, Jackson, who died Tuesday at age 84, was widely seen as the unofficial president of Black America. His many achievements are a tribute to his restless energy, audacious vision, moving eloquence and uncommon smarts. They came despite no small amount of skepticism from those who saw him as opportunistic and self-serving.

“What does Jesse want?” they would ask.

Jacques M. Chenet/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

His message of social justice, racial harmony and, yes, patriotism, gave him the moral authority to push doubt aside and repeatedly command the attention of the nation’s most powerful people and institutions. When he got their attention, he would put them on the spot, challenging old assumptions and old ways of doing things as he worked to pry free benefits for Black and poor people.

He mounted two surprisingly strong campaigns for the Democratic presidential nomination in both 1984 and 1988 that demonstrated the pivotal power of the Black vote and the multiracial appeal of his Rainbow Coalition. Jackson used the leverage he gained in those campaigns to demand that the Democratic Party reform its nominating process in ways that would make it easier for insurgent candidates to win and for Black votes to matter more.

In the late 1990s, Jackson began pressuring big financial firms and multinational corporations to hire and promote more African Americans, award more contracts to Black vendors and appoint more Black people to corporate boards. “Open up the walls on Wall Street,” Jackson demanded. And some of the big financial firms and corporate titans did, at least a little.

Business executives did not like being called out any more than political kingmakers, but through the years Jackson has won grudging participation from some major firms. He later mounted a similar effort in Silicon Valley.

When Jackson announced in late 1983 that he was traveling to Syria as part of a delegation seeking the release of captured Navy Lt. Robert O. Goodman Jr., a bombardier-navigator whose plane had been shot down, the Ronald Reagan administration resisted.

“Does Jesse know what he’s doing?” officials openly wondered. After Jackson returned with Goodman, President Reagan feted him from the White House.

Wally McNamee/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Goodman was amazed by the gumption of Jackson’s move, which he told Andscape in 2021 caught him totally off guard. A couple of weeks after he was shot down, Goodman said, he was rousted by his captors, who wanted to give him a haircut and a shave before he met an American visitor.

“Do you know Jackson?” they asked. “I didn’t know what the hell they were talking about,” Goodman said. “Michael? Reggie? Jesse?”

When Goodman met Jackson, he was relieved and quickly gained respect for him.

“It was good to know people knew where I was,” he said. “But as time went on, I was impressed by his tactical foresight. He has this folksy, calm demeanor. But even with that, you can see him calculating at 500 mph, trying to figure what is going to happen next.”

Decades later, Goodman, who lives in Colorado, remained awed by Jackson.

“That was a pretty ballsy move,” he said. “I don’t know too many people from a relatively minor base who would thrust themselves into international politics on a mission that had maybe a 20% chance of success.”

That is just one quality that sets Jackson apart. As a reporter, I have covered around a dozen events where Jackson spoke, and his ability to move crowds and capture big concepts in pithy phrases never disappointed.

“If my mind can conceive it and my heart can believe it, I know I can achieve it,” he would say. Frequently, he led his audience in chanting: “I am somebody!” To the ever-lingering question of what he wanted, Jackson would say, “I am just trying to take common sense to high places.”

More revealing, however, were the few private moments I shared with Jackson through the years. On several occasions, top editors summoned me to join private meetings with Jackson. Those sessions often reflected Jackson’s stature, even if they also exposed his organizational shortcomings.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Typically, he would show up unannounced, with urgent issues to discuss, but no fact sheets, or white papers or backup material other than his own trenchant observations. At times, busy editors may have been annoyed by the intrusions, but they always tried to make time for him.

His visit might be about the suspicious fires at Black churches across the South. Or the lack of a trauma center on Chicago’s South Side. Or the outcome of a peacemaking trip to Africa or the Balkans.

Before mass incarceration was widely seen as a scourge on the Black community, he would talk about traveling to cities around the country and repeatedly seeing new sports arenas and new jails. He talked about underfunded schools, the dignity of work and the corrosive impact of racism. He would observe that the persistent poverty in the rural South is a legacy of the region’s particularly racist history.

Other times, Jackson would telephone out of the blue with an announcement of one kind or another. As often as not, his visits and phone calls resulted in stories, helping propel issues he championed onto the national agenda.

With me, at least, his private remarks tracked his public ones. His informal conversations might include an unflattering observation about some person or another. On occasion, he sprinkled in a few curse words, which felt like his way of signaling that he was sharing the unvarnished truth. It certainly made Jackson more relatable.

For much of his career, Jackson was ever-present: leading marches, addressing rallies, speaking at political gatherings, opining on talk shows, joining picket lines, sitting ringside at fights and courtside at NBA games, receiving presidential awards, preaching from pulpits and appearing seemingly everywhere racial controversy made the news. That omnipresent quality sometimes made Jackson the target of mockery. Chicago newspaper columnist Mike Royko called him “Jesse Jetstream,” and the name stuck. But now it is clear that there was power in his presence.

“Rev. Jackson, he shows up. He may not be on the program but he’s going to be in Selma. He’s going to be in all the places where some important civil rights moment is happening. He’s kept that up,” Sherrilyn Ifill, the former president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, told me in September 2021. “He understands something that I admire and see as a valuable secret. People who are marginalized need to feel your consistency. We call it the ministry of presence.”

Perhaps Jackson’s ubiquity made it easy to take him for granted. But he was a historic figure who stood on the front lines of the fight for civil rights as it moved from ending state-sanctioned discrimination to the ongoing fight for equity in the workplace, the boardroom and the classroom.

Jackson was only four years removed from North Carolina A&T University, where he was a quarterback and student body president, and traveling with Martin Luther King Jr. when the famed civil rights leader was assassinated in 1968.

It was not long before Jackson emerged as the nation’s most prominent civil rights leader, one whose image reflected a new generation. Unlike his predecessors who wore sober suits and skinny ties, he was part of a new generation, comfortable in a dashiki, medallion and billowing Afro. He also moved the civil rights struggle into new arenas.

He threatened and led boycotts that helped Black entrepreneurs get fast-food franchises, car dealerships, and beer and soft drink bottling deals. Years later, he would insert himself into foreign policy discussions, pushing for the end of apartheid in South Africa and conducting negotiations to release prisoners in countries from Iraq to Cuba.

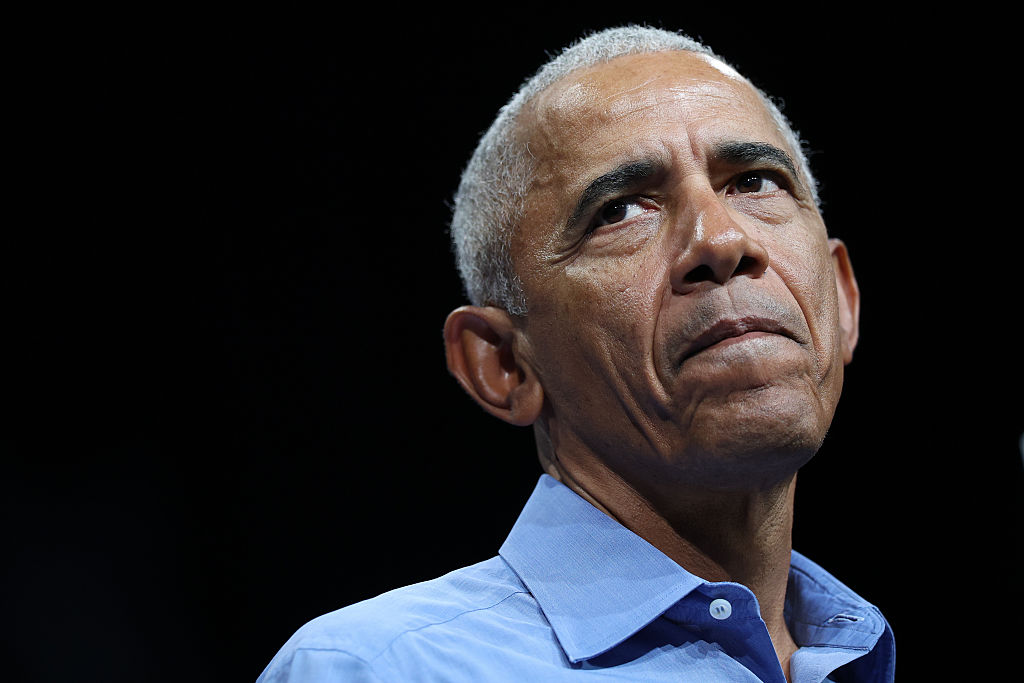

His two presidential runs helped clear the way for Black candidates to run elsewhere and, in 2008, for the election of Barack Obama as the nation’s first Black president.

“This idea of a Black candidate being able to develop this fusion support, which later was solidified by President Obama for sure, was first successfully accomplished by Rev. Jackson,” Ifill said. “He was able to pull together multiracial support.”

Part of Jackson’s political secret was the respect he showed for poor and working-class people, allowing them to be seen in their full humanity. That was the galvanizing force of his Rainbow Coalition. More than 30 years later, I can still remember feeling tears of pride welling in my eyes during his speech to the 1988 Democratic National Convention in Atlanta.

“Most poor people are not on welfare. Some of them are illiterate and can’t read the want-ad sections. And when they can, they can’t find a job that matches the address. They work hard every day,” said Jackson, who was born to a teenage mother in Greenville, South Carolina. “I know. I live amongst them. I’m one of them. I know they work. I’m a witness. They catch the early bus.”

The presidential runs may have marked the apex of Jackson’s influence. Still, in the subsequent years, he was as busy as ever. He served a term as a “shadow” senator from Washington. He endured a scandal in 2001, when he acknowledged fathering a child outside of his marriage with a woman who worked for the Rainbow PUSH Coalition. Despite that, he continued intervening in crises big and small, advising presidents, campaigning for political candidates and showing up wherever civil rights news was happening.

But slowed by age and illness, the attention he commanded slowly waned as yet another generation of leaders took the stage.

The last time I talked to Jackson face to face was in 2013. He was in a conference room at The Washington Post, where I worked at the time, finishing up one of his impromptu newsroom visits. He had a stack of glossy black-and-white photos, featuring him as a young man in rolled-up jeans and white sneakers as he walked along a corridor with King. He offered me a copy and asked me to remind him of my name so he could inscribe the photo.

He offered familiar encouragement. “Mike, Keep Hope Alive,” he wrote.

The post What did Jesse Jackson want? ‘To take common sense to high places.’ appeared first on Andscape.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0