The History Of Black Santa And Why Representation Matters

Black Santa has long occupied a complicated place in America’s holiday imagination. What many critics overlook is that the earliest depictions of a Black Santa were not celebratory: they were weapons of mockery aimed at the Black community. Over time, that image was reclaimed and reshaped. By the 1950s and 60s, Black Santa had evolved into a cultural and civil rights symbol.

Today, he still provokes excitement, joy, and, in some corners, controversy, but Black Santa remains a powerful symbol of representation, identity, and pride, reminding us of how far we’ve come.

Where does Black Santa come from?

The origins of Santa stretch back to the fourth century and the life of Saint Nicholas, a monk from the region now known as Turkey. The white version familiar to modern Americans, however, owes much to Thomas Nast’s late 19th-century drawings in Harper’s Weekly. It was during this era that some of the earliest U.S. portrayals of a Black Santa appeared, not as empowerment, but as part of minstrel entertainment and vaudeville traditions designed to ridicule Black people as inferior, according to The Tennessee Tribune and BBC News.

Contemporary accounts recall Christmas festivities enlivened by performers in “black face” dressed up as Santa singing “negro melodies.” One such story comes from 1915, when segregationist president Woodrow Wilson enjoyed a holiday celebration at a Virginia resort “presided over by a dusky Santa Claus,” according to the BBC. The story noted that, “Before [the tree] disported 15 negroes, whose antics and musical efforts kept the President and everybody else almost convulsed with laughter.”

The BBC also obtained a 1901 news clipping from Bloomfield, New Jersey, which reported: “A negro Santa Claus went down a chimney head first and landed on the fire. The surprised occupants of the room flogged him,” another attempt to exclude Black people from the holiday spirit of Santa.

From Negative to Positive: The transformation of Black Santa.

However, as the 20th century progressed, Nast’s imagery spread widely through Coca-Cola advertising in the 1930s and nationwide holiday marketing, and what followed were positive images of Black Santa that began to circulate. By 1919, the Pittsburgh Daily Post described what it called the first Black Santa “ever put on the streets of any city,” hired by Volunteers of America to connect with poor Black children. And in 1936, a major milestone arrived when tap-dancing icon Bill “Bojangles” Robinson became Harlem’s first Black Santa at an annual Christmas Eve party for underserved youth.

According to researcher E. James West, Black educators and civic reformers worked deliberately from the 1910s through the 1950s to safeguard and reshape the image of Black Santa. They, he explains, “saw the ‘Negro Santa Claus’ as a way of elevating Black self-esteem and countering racist versions of the character,” according to West’s 2023 journal article Searching for Black Santa: The Contested History of an American Holiday Tradition.

Notably, Blumstein’s, one of Harlem’s largest department stores, introduced its first Black Santa in 1943, influencing numerous downtown store owners who now catered to a predominantly African American customer base as white shoppers moved to suburban malls.

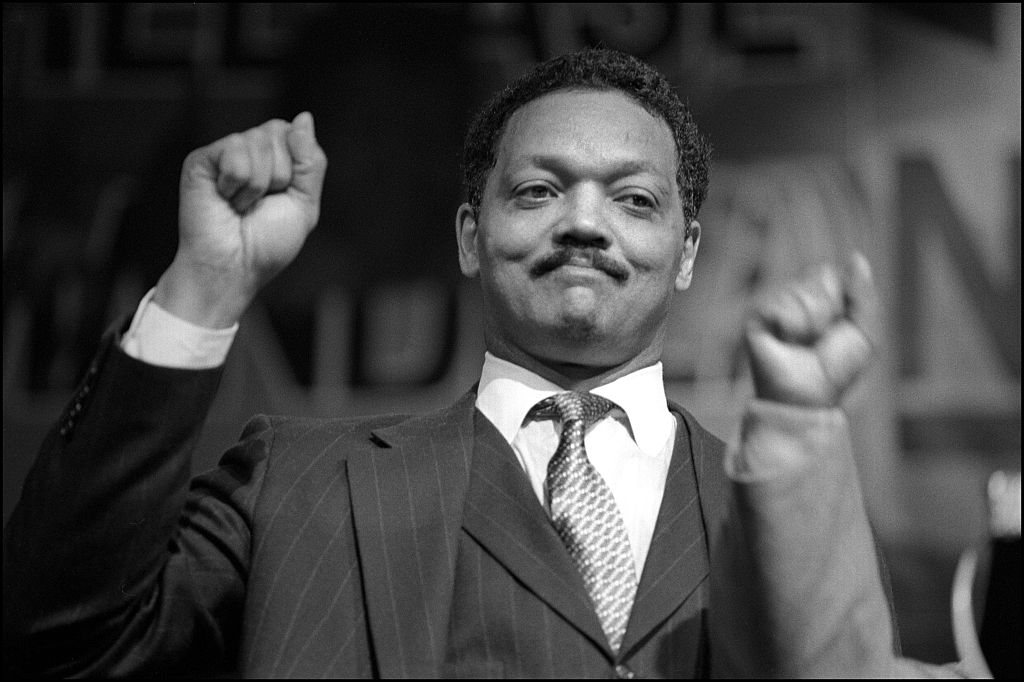

In the years after World War II, Black Santa became part of civil rights activism, appearing on parade floats, leading fair-housing marches, and serving as a visual protest against racial injustice.

West notes that “For some activists and business leaders, the ‘Civil Rights Santa’ that emerged in parallel with the postwar African American freedom struggle could promote ‘good interracial feelings in the community’, and for others he belonged on the frontlines of the battle for racial equality.” He adds that the later Black Power–era figure—often called the Black Power Santa or “Soul Santa”—served as a powerful emblem of Black cultural pride and economic self-determination.

By the 1960s, Santa had become a tool for civil rights groups using economic boycotts to push for equality. Notably, in 1969, civil rights leader Reverend Otis Moss Jr., a director for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), labeled Santa Claus “one of the established symbols of racism” during a dispute with Shillittoes, a Cincinnati department store that refused to hire a Black Santa.

Store owner Fred Lazarus III argued, “This has nothing to do with equality of employment. It just doesn’t fit the symbol as kids have known it.”

But the Rev. Otis Moss Jr. responded, “If a department store cannot conceive of a black man as Santa Claus for 30 days, it most assuredly cannot conceive of his being president or vice president for 365 days.”

The store relented the following year, a shift that spread across the U.S. in the early 1970s, eventually reaching Macy’s iconic New York flagship. As the movement broadened, some Black Power activists rejected Santa outright, seeing him as a figure steeped in white dominance. Others reinvented him, such as the Black Santa who appeared at the 1968 Chicago Black Christmas Parades wearing a black velvet dashiki and raising a gloved fist, echoing the protest of Olympians Tommie Smith and John Carlos. For decades, Black Santa has remained a political, cultural, and emotional lightning rod.

Representation matters.

Representation remains deeply important for children, who benefit from seeing themselves reflected positively in holiday traditions. As previously reported, research shows that when children of color encounter characters who look like them—on screen, in books, or during Christmas celebrations—it strengthens self-esteem and expands their sense of possibility.

In a December 2023 essay for The EveryMom, writer Daizha Rioland recalled the impact of a single Black Santa figurine in her grandmother’s home. The sight, she wrote, felt rare and transformative.

“Seeing a Black Santa was rare during my childhood, but I could always count on that one decor item to remind me that Santa didn’t have to be pale as snow, with blue eyes and rosy cheeks,” she wrote. “In fact, it was one of the few decor items that made me feel like Santa Claus might actually see me, know me, and stop by my house on Christmas Eve.”

So as the holiday season arrives once again, consider placing a Black Santa proudly atop your tree, a symbol of history, resilience, and the power of being seen.

SEE MORE:

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

![Le[e]gal Brief: Rev. Jesse Jackson Showed Us We Were Somebody](https://newsone.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2026/01/17682414196103.png?strip=all&quality=80&w=1024&crop=0,0,100,538px#)