The Colfax Massacre: The mass shooting that made America

OPINION: 150 years ago today, a white supremacist act of domestic terrorism set the stage for Black voter suppression, an insurrection and 150 years of gun reform stagnation The post The Colfax Massacre: The mass shooting that made America appeared first on TheGrio.

OPINION: 150 years ago today, a white supremacist act of domestic terrorism set the stage for Black voter suppression, the Jan. 6 insurrection and 150 years of gun hysteria.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

Boys, this is a struggle for white supremacy.”

Ku Klux Klansman Dave Paul, April 13, 1873

Whenever the subject of, well, anything having to do with politics, history or race arises, someone whose knowledge of America’s past is limited to the whitewashed version of history they learned in 11th grade will invariably respond by pointing out that “The Ku Klux Klan was Democrats.” Other versions include:

- “The Republicans freed the slaves.”

- “The Democrats were the real racists.”

- The GOP is the party of Lincoln

- What about …

Although those claims are easily refuted, a historian once taught me a too long; didn’t read version of the story of America’s political partisanship:

The Colfax Massacre.

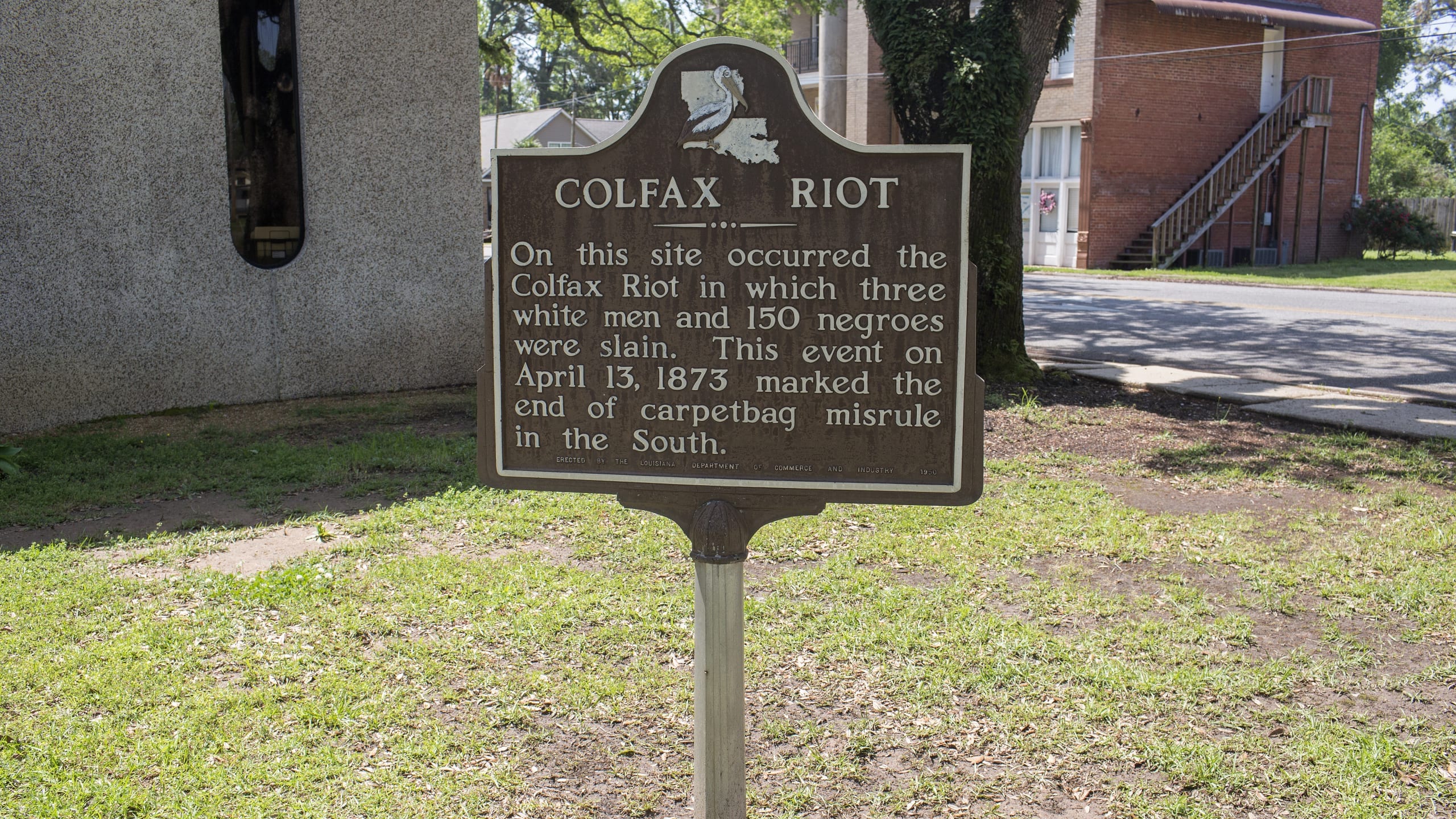

When a group dedicated to making America great again rallied at the capital of Grant Parish, Louisiana, 150 Easters ago, they were not representing political parties. They knew they were part of an insurrection. They were keenly aware that they were soldiers in the war for white supremacy. What this motley crew of Klansmen, former confederates and gun-toting White Leaguers did not know is that they were setting the stage for Jim Crow, school shootings and 150 years of debate over gun control.

They knew they were doing it for white people.

Insurrection Sunday

On Sunday, April 13, 1873, an armed brigade of Black men surrounding the Grant Parish Courthouse in Colfax, Louisiana, knew a fight was coming.

Newly elected State Rep. William Ward had already tried every imaginable way to avoid conflict, to no avail. Ward, a Black Union veteran, knew that the white minority hated the fact that he had been sent to the parish to control the racial terrorism in the surrounding area, so he sent a letter alerting the governor to impending trouble. Unfortunately, Ward’s messenger was captured by Klansmen Paul Hooe, Jim Hadnot and Bill Cruikshank, who had already issued a call for the sheriff to disperse the Black men. There was just one problem:

As far as Colfax’s Black citizens were concerned, there was no sheriff.

In fact, there wasn’t really a governor; there were two. In the 1872 election, Louisiana’s Liberal Republicans teamed up with Democrats to fight for white people’s voting rights (former confederates were forbidden from voting after the Civil War because of the whole treason thing.) The pro-white Fusionists claimed their candidate John McEnery won the 1872 election, while McEnery’s opponent, William Pitt Kellogg, also declared victory. McEnery, a former confederate soldier, enlisted the help of his fellow race warriors to create an entirely separate state government and put confederates in charge of voting across the state. So, depending on where you lived in Louisiana, you got to pick your governor. Most of the majority white parishes respected the authority of pro-white McEnery. In New Orleans and a few majority-Black parishes, the only governor they acknowledged was Kellogg.

Down in Grant Parish, the majority-Black electorate had outvoted whites 776-660, so they weren’t worried about those crazy election deniers. They had no idea McEnery’s Stop the Steal boys had sent fake certifications to the state government saying the pro-white candidates won Grant Parish by a landslide. When they heard rumors that the sheriff and judge they defeated at the ballot box had been sworn in anyway, the Black citizens of Colfax knew they had to take action (or, as I’m sure someone said, has a “trick for they a**”). On March 25, in the middle of the night, a makeshift Black militia of actual proud boys grabbed their guns and shovels, dug trenches around the courthouse and waited for the white people to show up.

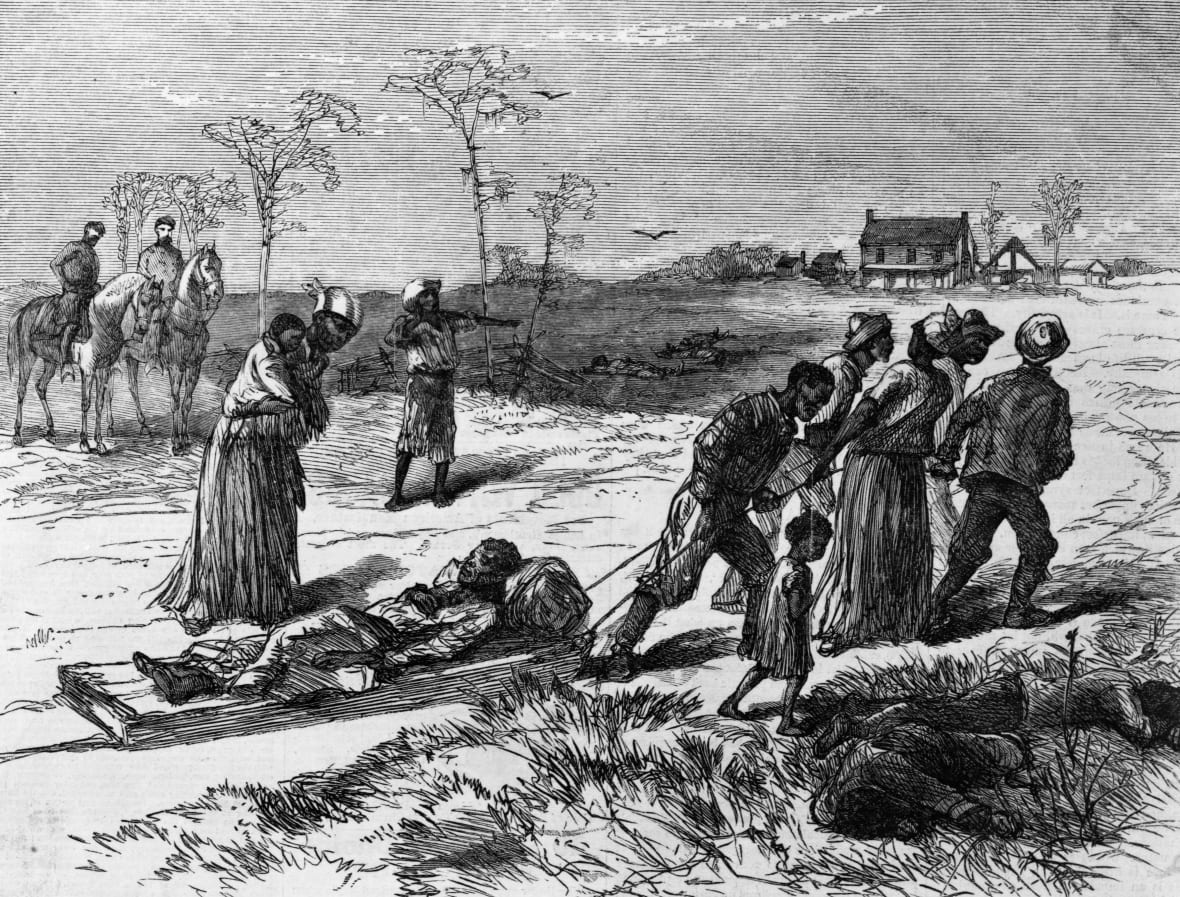

Remember, after the Civil War, Union troops occupied the Southern states to prevent white people from white people-ing. As the commanding officer of Company A, 6th Infantry Regiment of the Louisiana State Militia, Ward deputized a group of Black men to raid Cruishank’s, Hadnot’s and Judge William Rutland’s homes on April 5. Outraged that Black men were asserting their authority over their red-blooded whiteness, the trio of white men picked a random Black bystander, Jesse McKinney, and shot him in the head in front of his wife and children. McKinney’s wife, Laurinda, loaded him into a wagon “while the whites in the yard mocked them, hooting lecherously and calling them bad names,” writes historian LeeAnna Keith. The next day, it got even worse:

The Black women showed up.

They had guns, too. Outnumbered, Cruikshank and his boys sent out the call to Klansmen, confederate soldiers, the White League and any white man who believed in the supremacy of their skin color. Their clarion call included the worst fear of all:

Black men were going to have sex with white women.

“The Negroes at Colfax shouted daily across the river to our people that they intended killing every white man and boy, keeping only the young women to raise from them a new breed,” wrote George Stafford in a letter to the Louisiana Democrat.

“We were all startled and terrified at the news by a Courier who had just gotten in from our Parish Site,” recounted a citizen of a nearby parish. “[T]he Negroes under the leadership of a few unprincipled white men had captured the Court House & driven all white inhabitants out of the Town, were raiding stealing & driving the cattle out of the surrounding country. The Negro men making their brags that they would clean out the white men & then take their women folks for wifes.”

Meanwhile, on April 11, Ward fell ill from tuberculosis and had to leave the courthouse. On April 13, Easter Sunday, Christopher Columbus Nash, the new sheriff, came to the courthouse with 300 riflemen riding on horseback, dragging an automatic cannon that shot four-pound iron slugs and all the whiteness that ever was. He demanded that the Black men turn in their weapons and leave the courthouse. Most of the men who showed up were former confederate soldiers.

Now remember, the Black guardsmen had the approval of Ward, an elected state representative, a government-appointed official who was in charge of stopping insurrections. All the white men had were guns, a fake election and the imaginary authority provided by their whiteness.

The Black men did not move.

After giving the Black defenders 30 minutes to remove the women and children, the white men opened fire. The first cannon shot tore through the abdomen of Adam Kimball, who ran inside the courthouse before his intestines fell on the courthouse floor. The supremacists mowed down the defenders of democracy and burned down the courthouse. When the smoke cleared, between 50 and 280 Black men were dead, according to Keith. No one knows for sure how many. Some of the bodies were tossed into the Red River and buried in unmarked graves. Others were burned.

Three white men had been killed.

And Justice for None

The Colfax Massacre is not important because it was the single bloodiest incident in the bloodiest period of American history. It created the America we know today.

Unlike most of America’s racial massacres, 97 of the paramilitary forces were indicted by the Supreme Court under the recently passed Enforcement Acts. Also known as the Ku Klux Klan Acts, the laws prohibited groups of white supremacists from going “in disguise upon the public highways, or upon the premises of another” with the intent to violate the rights of other people. Three men were found guilty, but the judge unilaterally overturned the conviction and released the murderers on bail. When the Department of Justice appealed, the Supreme Court overturned the convictions in the landmark case United States v. Cruikshank.

How?

See, the men were indicted for denying the Black citizens their right to bear arms for a lawful purpose. The justices ruled that the Enforcement Acts actually robbed the Klansmen of their right to bear arms and peaceably assemble. Furthermore, they noted the 14th Amendment only granted Black people equal protection from the federal government. It did not protect formerly enslaved people from individual or even state-sponsored racism.

Why was this important?

Well, imagine if you had oppressed people for more than 250 years and were looking for a way to continue it. Imagine if the highest judicial authority in the land told you that taking away a group’s constitutional rights was perfectly fine as long as it wasn’t an act of Congress.

Ladies and gentlemen, meet Jim Crow.

This is the loophole that created segregation. This is why Southern states could write constitutions that disenfranchised Black voters. This is how unequal schools and voter suppression and Black codes and the era known as Jim Crow came to be. As the Smithsonian Magazine notes:

This ruling essentially neutered the federal government’s ability to prosecute hate crimes committed against African-Americans. Without the threat of being tried for treason in federal court, white supremacists now only had to look for legal loopholes and corrupt officials to continue targeting their victims, Gates reports. Meanwhile, principles of segregation were beginning to work their ways into law, with Plessy v. Ferguson officially codifying “separate but equal” just 20 years later.

Smithsonian Magazine

But there was one more thing.

Remember that part about illegally taking away Black people’s guns? Well, the Supreme Court didn’t really debate that part. In fact, the Supreme Court had never decided a case based on the Second Amendment. Before Cruishank, the general consensus was that the Second Amendment authorized militias to carry firearms. But the court essentially ruled that “the right to keep and bear arms exists separately from the Constitution and is not solely based on the Second Amendment, which exists to prevent Congress from infringing the right.”

The justices believed that everyone had the right to own a gun, and Congress couldn’t do anything about it.

The Colfax Massacre wasn’t the first racial massacre or its deadliest. But the events of April 13, 1873 begat the Cruikshank, which begat the end of the Enforcement Acts, which begat the Compromise of 1877, which begat the removal of federal troops from the South, which begat Jim Crow, which begat separate but equal, which begat redlining, which begat unequal schools, which begat mass shooting after school shooting after racist shooting after white supremacist insurrection.

For 150 years, America’s inequality has rested upon this bloodstained pillar of injustice. And whenever anyone tries to do anything about it, the name of the man who helped spark a racist massacre is resurrected. Not even Ron DeSantis and all the critical race theory laws in the world will never erase the memories of the Black resistance that happened in Colfax. And if you ever wonder why we can’t do anything about school shootings, remember Cruikshank …

He is risen.

Michael Harriot is a writer, cultural critic and championship-level Spades player. His book, Black AF History: The Unwhitewashed Story of America, will be released in September.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!

The post The Colfax Massacre: The mass shooting that made America appeared first on TheGrio.