South Carolina’s Critical Race War on Education, Part 1: Origin story

OPINION: To commemorate the anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, theGrio's four-part series explores how South Carolina became the home of the fight against education equity and critical race theory. The post South Carolina’s Critical Race War on Education, Part 1: Origin story appeared first on TheGrio.

OPINION: To commemorate the anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, theGrio’s four-part series explores how South Carolina became the home of the fight against education equity and critical race theory.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

There is an African-American adage that was as true during the brief two-and-a-half century era of race-based enslavement as it was the day four million pieces of human chattel were magically transformed into second-class citizens. As an axiom, it embodies the American sentiment euphemized as racial resentment, economic anxiety or plain-old “white backlash.”

“When white America catches a cold, Black America catches pneumonia.”

But if such a thing as “Black America” exists, then where is its capital? Washington, D.C., is the capital of all of America; Brooklyn has been recently gentrified and, according to the research of noted geographer Omeretta the Great, the headquarters of African America “is not Atlanta.” So, where is the place that holds the history of Africans in America and center of operations?

South Carolina is the capital of Black America.

Even before 13 colonies united as America, the Palmetto State served as a breeding ground for Black resistance and an innovation hub for white supremacy. Scholars estimate that 40% of the country’s enslaved Africans disembarked on the shores of the “slave capital of North America.” The “cradle of the confederacy” hosted the opening games of the nation’s first official white supremacist insurrection and had a majority-Black population for most of its existence. The history of Black resistance, racial resentment and white supremacy in general begins with the history of South Carolina.

Sixty-nine years ago this week, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race” deprives Black children “of equal educational opportunities.” Although the “Board of Education” part of Brown v. Board of Education references a Topeka, Kansas, school district, the landmark ruling actually combined five different civil rights cases. Briggs v. Elliott, the first of the cases that declared unequal education violated the constitutional rights of Black Americans, was filed in South Carolina.

“When you talk about educating Black students, you have to start with the resistance to Black education,” Dr. Gloria Swindler Boutte told theGrio. “You can’t understand one without understanding the other.”

If someone designed an imaginary enemy to rally their troops for the war on critical race theory, wokeness and history-induced tummy aches, Dr. Gloria Swindler Boutte would be the perfect archetype. As the founder and executive director of the University of South Carolina’s Center for the Education and Equity of African American Students (CEEAAS), she could serve as the poster child for “wokeness.” She is also U.S.C.’s associate dean of diversity, equity and inclusion and is a fierce proponent of culturally relevant teaching. For more than three decades, Boutte has traveled the world, espousing the need to integrate culturally sensitive teaching methods into classroom strategies — especially for those who teach African-American students. Of course, her approach embodies everything that ultra-conservative culture warriors hate. And, because she lives in South Carolina, she was one of the first targets of this new culture war.

Over the course of this four-part series, theGrio will delve into the origins of the newest attack on equal education — critical race theory. You will meet the Black educators affected by this anti-Black conflict, the villains who fired the opening salvo and the heroes fighting the not-so-cold war on CRT.

It is critical.

It is about race.

It is not a theory.

Absolute Power and Authority: A race war origin story

In August 1669, 50 years after “20 and odd negroes” became beta-testers for government-sanctioned, race-based, intergenerational chattel slavery, three ships set sail for Charles Town at Albermarle Point in the Americas. Along with 150 or so passengers, the three vessels also carried the Fundamental Constitutions, which included the clause that would forever codify white supremacy as a governing principle. Known as Article 110, the provision stated: “Every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves, of what opinion or religion soever.”

White supremacy was embedded in South Carolina’s foundation, and since the beginning, Black people wanted to be free. These fundamentally opposing principles would fuel a back-and-forth fight for freedom that would shape institutional anti-Blackness across America.

And yes, it was a war.

In 1739, a literate African led the largest slave revolt in colonial history. After the Stono Rebellion, the state’s General Assembly passed the Negro Act of 1740 to control “disobedient and evil-minded Negroes and other slaves.” Nearly every colonial slave code was based on that South Carolina law that fined “all and every person and persons whatsoever, who shall hereinafter teach or cause any slave or slaves to be taught, to write.” And, because Black people were chattel, the Negro Act was considered property law; it withstood judicial scrutiny for 120 years.

In the 1820s, white Charlestonians burned Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church to the ground after Denmark Vesey, a literate free Black citizen, was accused of planning a revolt and teaching the Black congregants to read. Meanwhile, lawmakers built a municipal guard to “fortify Charleston against future slave rebellions,” creating an academy for slave patrollers that became a heralded military college, the Citadel. After Emancipation, the majority-Black delegation at the 1868 South Carolina constitutional convention created the one thing they thought could ensure their future prosperity for all:

The “first, free, compulsory, statewide public school system in America,” according to Michael Boulware Moore, president of South Carolina’s International African American Museum.

When whites regained control of the state legislature in 1876, they rewrote the state’s constitution and passed laws mandating racial segregation. Today, the state ranks 42nd in overall education, and the K-12 system ranks 45th in racial equality. The Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights found that Black students in South Carolina are three times as likely to face out-of-school suspension and four times more likely to be expelled than their white counterparts. Despite being the fifth Blackest state in America, Black taxpayers in the Palmetto State help fund one of the five whitest state university systems in America.

And because of history, demographics and the principles embedded in South Carolina’s DNA, it seemed like the disparities would continue forever unless something happened.

Something happened

In June 2021, Dr. Boutte held a virtual training session for teachers in Kershaw County School District (KCSD). The school board had just added courses in African-American history and African-American literature to its curriculum, and in Boutte, KCSD had chosen one of the world’s leading experts to educate its teachers.

“They started filing complaints saying that I was teaching critical race theory,” Boutte told theGrio. “I don’t teach critical race theory; I was teaching them how to teach African-American history. But [a parent] called a meeting and just profiled me. She said that I was teaching critical race theory, that the district is acquiring for teachers to adopt my books, which is really not true, and basically that I was pretty much like the antichrist.”

While Boutte was familiar with critical race theory, she had no idea why anyone would accuse her of teaching graduate-level methods of examining social structures through the lens of race. Days later, Boutte’s name popped up on a right-wing website’s list of educators “willing to violate the law to keep pushing CRT.”

That same summer, Berkeley County Schools hired Deon Jackson as its first Black superintendent. Not only was a Black man now in charge of the fourth-largest school district in the state, but Jackson earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the Citadel, the institution built from white fear.

When Jackson began his tenure, Dr. Baron Davis was already entering his fourth year as superintendent of Richland County School District Two, the state’s fifth-largest district. By then, Davis was already making national headlines by challenging the state’s conservative policy banning mask mandates.

Jackson and Davis, both of whom I’ve known for more than two decades, were not just the first Black superintendents in two of the oldest counties in the state; they were dedicated to improving outcomes for Black students. From behind the front lines, they began hiring Black teachers, implementing their plans for equity and spreading their vision for a system of equal education. They signed contracts with CEEAAS to prepare their teachers. And, in the wake of the “racial reckoning” during the 2020 George Floyd protests, school districts across the state followed Jackson’s and Davis’ lead, pledging to create a more inclusive curriculum. It appeared as if the equal education that Black South Carolinians had struggled to create was finally happening.

This new crop of skilled Black educators was taking charge of public school boards and instituting policies aimed at erasing the educational disparities that plagued South Carolina for three centuries. Three of the five largest school districts in South Carolina had Black superintendents on the first day of the 2021 school year. And, According to state data, when students returned to classrooms in the fall of 2020 after an extended COVID-19 shutdown, for the first time in history, white children were minorities in South Carolina’s public school system.

Then it all fell apart.

Contrary to popular belief, this movement had nothing to do with concerned parents, critical race theory or “woke” educators. It was not about a “leftist agenda” or conservative values. It was about something else entirely.

Something else

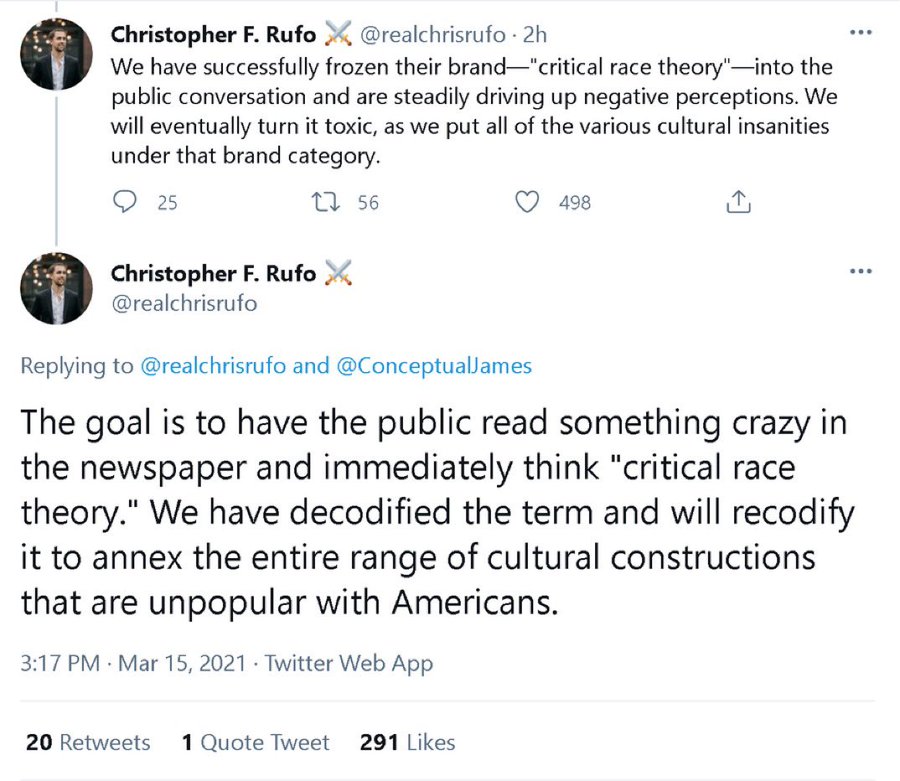

“I am quite intentionally redefining what ‘critical race theory’ means in the public mind, expanding it as a new catchall for the new racial orthodoxy. People won’t read Derrick Bell, but when their kid is labeled an oppressor in the first grade, that’s now CRT.”

— Christopher F. Rufo

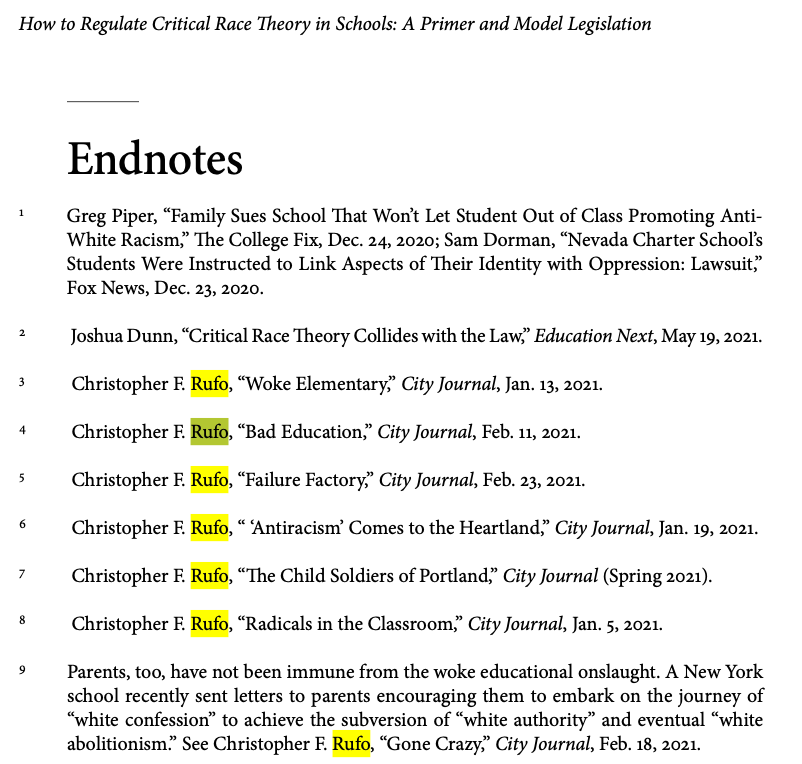

In August 2021, legal analyst James Copland published a paper for the Manhattan Institute, a far-right think tank where Christopher Rufo serves as a senior fellow. Titled “How to Regulate Critical Race Theory in Schools,” the paper offered a template for lawmakers who wanted to ban the nonexistent practice, redefining critical race theory according to four “core concepts or beliefs.”

- “That the United States or the state is ‘fundamentally and irredeemably racist or sexist’”;

- “That individuals are ‘inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive’ by virtue of ‘race’ or other intrinsic characteristics whether consciously or unconsciously”

- “That individuals are personally ‘responsible for actions committed in the past by other members of the same’ race or other intrinsic characteristics; and”

- “That individuals’ ‘moral character is necessarily determined’ by race or other intrinsic characteristics”

None of these tenets are actually fundamental to critical race theory or even mentioned in CRT’s graduate-level pedagogy. When theGrio reviewed more than 60 anti-CRT bills in 40 states, we could not find a single piece of proposed legislation that did not include all or most of the precepts from the Manhattan Institute’s model legislation. What we found hidden in the end notes of the Manhattan Institute’s ant-CRT legislative template was the name of patient zero. While Kimberlé Crenshaw, Richard Delgado and other experts on critical race theory were mentioned, the Manhattan Institute’s anti-Black education template cited the anti-Black ideology of one man more than any other: Christopher F. Rufo.

Christopher Rufo is not an authority on anything.

Despite having no formal education, training or experience in academics, history or teaching students, the far-right activist somehow parlayed a make-believe master’s degree from Harvard University into a position as the senior fellow and director of the initiative on critical race theory at the Manhattan Institute. In an effort to smother state-sponsored diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis recently appointed Rufo to the board of trustees at the New College of Florida.

Rufo — who did not respond to theGrio’s requests for an interview — gained these accolades partly by pushing a soft version of white nationalism to an already antagonized white populace worried that affirmative action, immigration reform and diversity efforts would destroy the superior Western civilization created and maintained by America’s majority. Along with conservative co-conspirators such as Tucker Carlson, Megyn Kelly and politicians who appeal to the growing population of people who believe that anti-white discrimination is increasing, Rufo found a catchphrase that would symbolize the plague of white oppression.

“We’ve needed new language for these issues,” Rufo told the New Yorker. “‘Political correctness’ is a dated term and, more importantly, doesn’t apply anymore … The other frames are wrong, too: ‘cancel culture’ is a vacuous term and doesn’t translate into a political program; ‘woke’ is a good epithet, but it’s too broad, too terminal, too easily brushed aside. ‘Critical race theory’ is the perfect villain.”

It might sound evil, but the effort to redefine critical race theory worked. Again, every single law and executive order banning critical race theory examined by theGrio contained excerpts that were directly copied and pasted from the Manhattan Institute’s sample legislation.

The magic trick

“We have successfully frozen their brand — ‘critical race theory’ — into the public conversations and are steadily driving up negative perceptions,” Rufo tweeted in March 2021. “We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category. The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’”

But Rufo wasn’t just a founding father of the campaign against critical race theory; he redefined it. He claimed that a Treasury Department diversity training session taught employees that “all white people uphold the system of racism and white superiority.” Pointing his scare tactic at Fox News viewers, Rufo said lessons on intersectionality “reduces people to a network of racial, gender and sexual orientation identities with white straight men “at the top of this pyramid of evil.”

In May 2021, three months before the Manhattan Institute published its sample legislation, exactly 45 days after Rufo bragged about “redefining what it means in the public mind,” the S.C. House Committee on Education and Public Works introduced two bills. The first was House Bill 4325, to “provide public school districts, public schools and public institutions of higher learning” with a template for redefining critical race theory. The next day, state Rep. Bill Taylor of Aiken, S.C., introduced House Bill 4343. Known as the “Academic Integrity Act of 2021,” the bill was the first of five anti-CRT bills in the state assembly that proposed to withhold funds from any school or organization that teaches Rufo’s “core concepts or beliefs.” While the bills failed on technicalities, this power and authority would continue.

On Feb. 8, the South Carolina House passed a revised version of HB 4325. Although the South Carolina Transparency and Integrity in Education Act did not mention the words “critical race theory,” it included every single one of Rufo’s principles:

The following prohibited concepts may not be included or promoted in a course of instruction, curriculum, assignment, instructional program, instructional material (including primary or supplemental materials, whether in print, digital, or online), surveys or questionnaires, or professional educator development or training, nor may a student, employee, or volunteer be compelled to affirm, accept, adopt, or adhere to such prohibited concepts:

- one race, sex, ethnicity, color, or national origin is inherently superior to another race, sex, ethnicity, color, or national origin;

- an individual, by virtue of the race, sex, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin of the individual, inherently is privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously;

- an individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment because of the race, sex, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin of the individual;

- the moral character of an individual is determined by the race, sex, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin of the individual;

- an individual, by virtue of the race or sex of the individual, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race, sex, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin;

- meritocracy or traits such as a hard work ethic:

(a) are racist, sexist, belong to the principles of one religion; or

(b) were created by members of a particular race, sex, or religion to oppress members of another race, sex, ethnicity, color, national origin or religion; and

- fault, blame, or bias should be assigned to race, sex, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin, or to members of a race, sex, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin because of their race, sex, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin.

South Carolina lawmakers had simply cut and pasted Rufo’s definition of critical race theory.

Rufo had magically “redefined what ‘critical race theory’ means … expanding it as a new catchall for the new racial orthodoxy.” Using nothing but the racism hidden under his hat and the blindfold of whiteness, he had hoodwinked conservatives into believing that the state’s K-12 teachers — 78% of whom were white — were teaching kids to hate white people. He had managed to abracadabra a complex legal perspective into a living, breathing demon.

“They engineered this whole crisis,” said Boutte. “I think that the engineers know exactly what they’re doing. I think they know that they’re misrepresenting what culturally relevant teaching is. They’re not fighting critical race theory. Yes, they’ve just created this wrong definition but there’s no use in explaining the definition. The goal really is to keep whiteness centered; to move us back in time.”

Of course, if the race warriors fighting against equal education were going to be successful, convincing politicians wouldn’t be enough. They would need to solicit rank-and-file white parents in South Carolina to their centuries-old cause, and to do that, they needed a modern-day Emanuel and villain who was responsible for teaching “disobedient and evil-minded negroes.”

So, of course, they came for Dr. Boutte first.

In part two of our series, you’ll see exactly who came for Dr. Boutte, how they did it and what it looks like when someone exercises “absolute power and authority.”

Michael Harriot is a writer, cultural critic and championship-level Spades player. His book, Black AF History: The Unwhitewashed Story of America, will be released in September.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!

The post South Carolina’s Critical Race War on Education, Part 1: Origin story appeared first on TheGrio.