Skipping Meals And Carrying On: How Howard Students Are Still Normalizing Hunger After SNAP Disruptions

It has been just over a month since the federal government reopened after a weeks-long shutdown that threatened to cut off food assistance for millions of Americans. Lawmakers declared the crisis averted. SNAP benefits, they said, would resume. Normalcy, at least on paper, had returned.

But for many college students, including those at Howard University, the sense of relief never fully arrived.

During the shutdown, more than a million college students nationwide who rely on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program faced uncertainty about whether they would be able to afford groceries. Some experienced reductions or delays in their benefits. Others worried they would lose access altogether. And even after the government reopened, the instability exposed how fragile students’ access to food already was.

As the semester winds down and winter settles in, many students are still bracing for what could be a difficult season of stretching meals, skipping dining halls, and relying on campus pantries to fill the gaps left by inconsistent federal support.

At Howard, hunger and abundance exist side by side.

Inside the Blackburn University Center, the campus’s central student hub, students pass a cafeteria, a Chick-fil-A, a popular takeout spot, and several convenience-style markets designed to ensure no one goes without food. That is, if they can afford it. When ‘meal swipes’ or ‘dining dollars’ run out, options narrow quickly.

What happens next often depends less on availability than on access, who you know, what resources you know about, and how comfortable you are asking for help.

Tucked just off the main entrance sits HU Nourish Pantry, the university’s only free food option. The pantry provides canned goods, toiletries, and, when available, fresh produce to food-insecure students. It serves about 400 appointments a month and relies heavily on donations, a model that pantry director Eryka Byrd says is increasingly strained as federal nutrition benefits fluctuate and student need grows.

“We’re seeing more students who are unsure what support they’ll have from month to month,” Byrd said. “And when that happens, campus pantries become a lot more than a backup plan.”

Howard students’ anxiety reflects a broader national problem. More than 1.1 million college students rely on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, to afford groceries each month, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Nearly one in three U.S. college students experiences some level of food insecurity, with higher rates at HBCUs, where students are more likely to come from low-income households or receive Pell Grants. Many HBCUs already operate with limited resources, leaving students particularly vulnerable when federal benefits are delayed, reduced, or difficult to access.

For Morgan Stephens, a senior journalism major, SNAP has been essential to staying fed during the school year. Stephens typically receives $144 a month in benefits. After moving off campus this fall, she opted out of Howard’s meal plan, priced at more than $1,200 per semester, and relied instead on meal prep and grocery shopping.

Last month, her benefits were cut in half.

“The impact was immediate,” Stephens said. “I’ve been on campus a lot, so I’ve been digging in my pockets or asking my mom, ‘Hey, I’m hungry, can you send me $20 so I can grab something to eat?’”

Where containers of home-cooked meals once filled her backpack, Stephens now relies on fast food and the occasional dinner invitation from friends. McDonald’s, she said, has become a necessity rather than a preference.

“It’s cheap,” she said. “Even though I don’t really want it, I know I need to eat.”

For students like Stephens, losing even part of a SNAP benefit means reshaping daily routines around what they eat, how long they stay on campus, and how often they ask for help. But many Howard students never qualified for SNAP. A 2024 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that in 2020, fewer than two in five food-insecure college students met eligibility requirements for SNAP. Of those who did qualify, 59 percent reported not receiving benefits.

Those students are the reason HU Nourish Pantry exists.

Founded in 2018, the pantry is open to any actively enrolled Howard student, from first-year undergraduates to law students on the West Campus. There are no income requirements or eligibility screenings beyond enrollment.

“That was intentional,” Byrd said. “People come for different reasons. Yes, there’s economic need, but some students have dietary restrictions, some can’t use their meal plans because of schedules, and others just need flexibility.”

Despite widespread need, the pantry operates with limited capacity. Appointments are required, shelves depend on donations, and staffing is primarily made up of student workers. When supplies run low, there is little ability to restock beyond what donors provide.

With the semester ending and uncertainty around federal nutrition assistance continuing, Byrd said the pantry is bracing for increased demand.

“It’s a juggling act,” she said. “We want to offer more appointments and more variety, but we also don’t want students to show up and find empty shelves.”

Food access around Howard has also grown more complicated as nearby dining options have disappeared. Several popular restaurants along Georgia Avenue, including Chipotle, Subway, Potbelly, and Negril, closed down in recent months. Outside of campus cafeterias, the nearest option for fresh, prepared food is a Whole Foods Market, which many students say is out of reach on a college budget.

Naisha Fletcher, a Howard student whose family immigrated from Haiti, grew up relying on SNAP. While she no longer draws directly from her family’s benefits, limited food access on and around campus has made hunger a familiar presence in her college life.

“It doesn’t look dramatic,” Fletcher said. “It’s skipping breakfast to make an 8 a.m. class, realizing at night that all you’ve had is water, or walking past the dining hall knowing you can’t afford anything inside.”

For Fletcher, recent disruptions in SNAP didn’t create a new crisis. They deepened an existing one.

Students experiencing food insecurity say they often normalize hunger, especially at academically demanding institutions like Howard, where pressure to perform leaves little room to slow down. Some describe choosing between transportation home and buying lunch. Others juggle phone bills, textbooks, and groceries. As the semester draws to a close, many say the stress of finals compounds the strain of uncertain access to food.

University pantries like HU Nourish have increasingly shifted from supplemental resources to essential lifelines. But those lifelines remain fragile. Without consistent donations, institutional funding, or expanded partnerships, the pantry must constantly negotiate how to meet growing needs with unpredictable supplies.

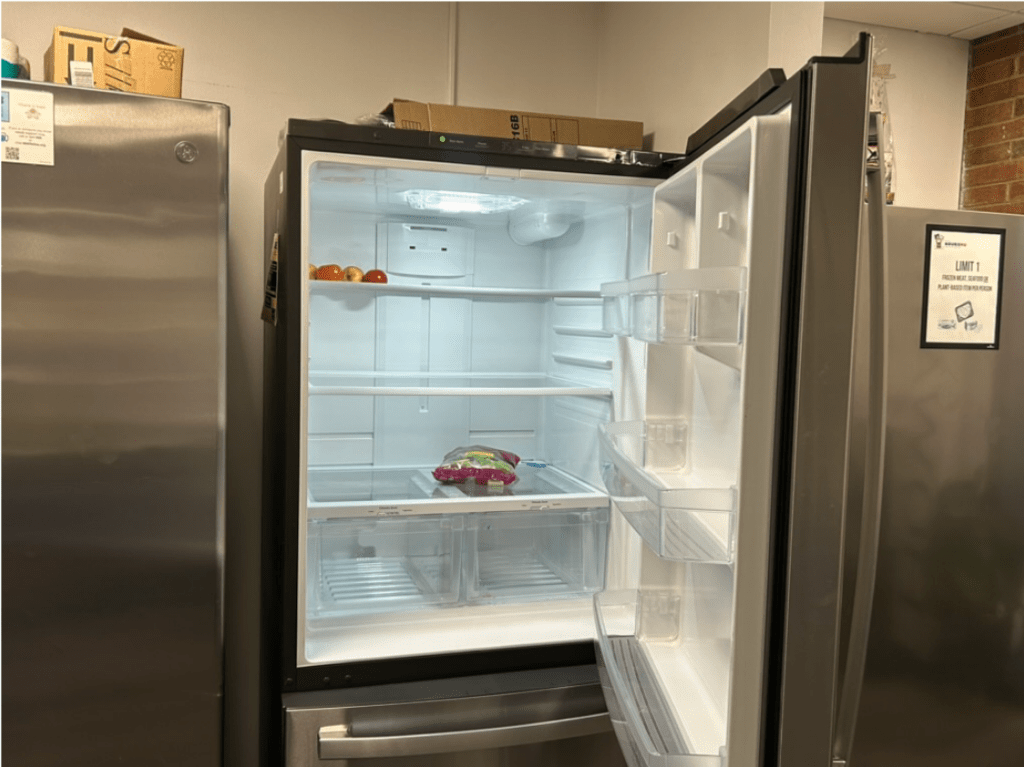

Earlier this week, students walking into HU Nourish found shelves thinner than usual. Canned goods were spaced farther apart, and the refrigerator that once held fresh produce contained only a bag of salad greens and a single apple.

Byrd said moments like these underscore what is at stake.

“It’s hard for students to think, function, and thrive when they’re hungry,” she said. “A nourished mind works better. A nourished spirit rises better. There are already enough stressors on campus—worrying about food shouldn’t be one of them.”

Zoe Cummings is a senior honors journalism major and Spanish minor at Howard University, covering HBCU news, politics, and culture. You can follow her on Instagram @zoesxphia.

SEE ALSO:

‘Empathy Is Hard To Find In The Big House.’ A Howard Student Fears SNAP Cuts Ahead Of The Holidays

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0