NaVorro Bowman Jr. is forging a separate path from his NFL dad

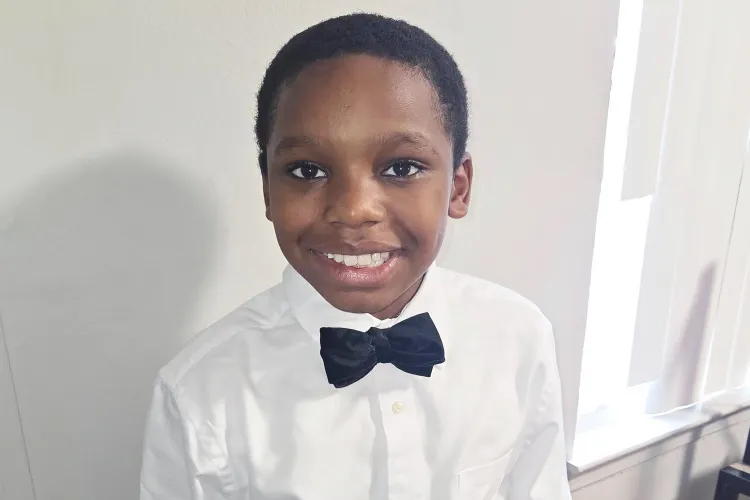

A dejected, 9-year-old NaVorro Bowman Jr. stared at the car’s passenger-side floor mats as tears inched down his cheeks after his first tryout with the Team Takeover AAU basketball program in Washington, D.C.

When the coach had the best players scrimmage at the end of the session, he abrasively instructed Bowman to take a seat against the wall.

As Bowman and his mom drove away from the gym, he sobbed and said he didn’t want to play basketball anymore.

“I was going as hard as I could, and when the coach told me to sit while everyone else was playing, I was going through all types of emotions,” Bowman recalled.

Playing against those seasoned Team Takeover kids proved more difficult than slam dunks on the mini-hoop in the San Francisco 49ers Kids Room at Levi’s Stadium while his father, NaVorro Bowman Sr., forged his legacy as one of the greatest linebackers in franchise history.

“Little NaVorro could move his feet because he played soccer,” said his mother, Mikale Bowman. “He was really good at defense, but had problems getting the ball up the court. He also couldn’t shoot very well. He was crying. He felt defeated.”

He didn’t stay that way. Bowman Jr. has since developed into one of the nation’s premier high school basketball prospects in the Class of 2027.

The 6-foot-3 junior guard, ranked No. 46 in the 2027 ESPN SCNEXT 60, is starring for Notre Dame High School, which plays Sierra Canyon High on Friday in a boys’ basketball game between two of California’s top teams (ESPN2, 11:30 p.m. ET).

Bowman Jr. holds scholarship offers from UCLA, USC, Villanova, Cal, TCU and his father’s alma mater, Penn State, among others.

“I’ve been blessed to coach a lot of high-level kids,” Notre Dame head coach Matt Sergeant said. “I don’t know if I’d rank anyone higher than NaVorro in terms of his desire to compete. He wants to win every drill, fights for every inch on the court, and accepts coaching. And he’s a smart, funny kid with an innate Magic Johnson-type joy that can light up any room.”

Bowman Family

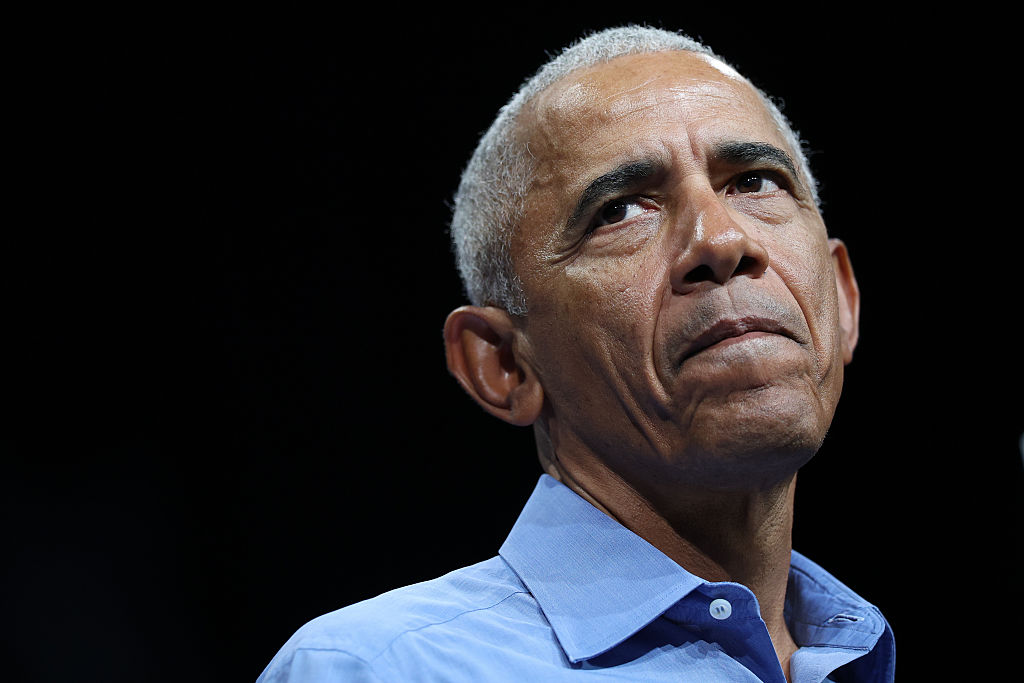

After that Team Takeover tryout, Mikale took matters into her hands and called her husband. Bowman Sr. was finishing his final NFL season in 2017, his lone year with the Oakland Raiders, capping an eight-year career that saw him earn four first-team All-Pro honors.

Soon to return to the family’s Maryland offseason home, Bowman Sr. received an edict regarding his son’s athletic trajectory.

“If you don’t coach him, he’s not playing,” Mikale told her husband.

Team Takeover fielded two teams heading into that spring and summer. They included some of the best youth basketball players in the D.C. area — a Red squad and a Black one.

Bowman Sr. volunteered to coach a developmental squad called the Gray team. It was for kids — like his son — who weren’t polished. At the end of that summer, after the Red and Black teams were eliminated from the AAU national championships, the Gray team continued to advance, and it eventually placed ninth in the country.

“NaVorro Bowman Sr. is a patient, excellent coach and teacher who instilled confidence in all of those kids,” Mikale said. “Each week, you could see them improving.”

Bowman Jr.’s rapid development didn’t go unnoticed.

“He had some athleticism, played extremely hard and challenged himself to stop his man from scoring,” Bowman Sr., 37, said. “His best trait was that he was a competitor.”

Heading into nationals that year, the much-improved Bowman Jr. was asked to join the Black squad.

“It felt great to grow with the kids who supposedly weren’t good enough to play on the so-called best travel teams,” Bowman Jr. said. “So when they asked me to jump over to the Black team, I was like, ‘Nah, y’all cut me. I’m good.’ ”

Notre Dame High School

To accelerate his son’s basketball education, Bowman Sr. reached out to a couple of old friends. One was Patrick Robinson, the ball-handling wizard and D.C. playground legend more popularly known as Pat Da Roc. The other was Keith Williams, a renowned trainer who has tutored the likes of NBA players Kevin Durant, DeMarcus Cousins and Markelle Fultz, among others.

“Players from the DMV [District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia] are gritty, they go hard. So I had to learn how to play physical and get tougher mentally” said Bowman Jr. “Training with Pat got my handles tight. It was a masterclass in the use of hesitation dribbles. With Keith, it was about fundamentals, repetition and mastering pull-up jumpers off the dribble. The better I got, the better I wanted to get.”

Williams knew Bowman Sr. when he was an adolescent competing against some of the area’s top high school and college basketball players at the 24-hour Run-N-Shoot facility in District Heights.

“Most people don’t realize how good he was at basketball,” said Williams. “NaVorro was an incredible defender with quick feet. He had natural instincts and anticipation. During his NFL offseasons, he’d be in the gym with us holding his own against NBA guys.”

Williams had to temper Bowman Sr.’s timeline and expectations, though, urging patience as it related to his son’s development.

“I got Little NaVorro when he was 9 years old, and he was such a nice kid,” said Williams. “I told his dad, ‘Here’s the problem: There’s no way he’s going to be as hungry as you were at that age. You came up rough, in a one-story house with two rooms and seven people. You can’t duplicate that. He ain’t hungry right now. But he’ll get there.’ ”

Bowman Sr.’s hunger was born from necessity. He grew up along two older brothers in tough Suitland, near D.C. His father worked at the electric company and moonlighted as the neighborhood mechanic. His mother managed a nearby Wendy’s.

“I absorbed their work ethic while also being aware of what was going on around me,” Bowman Sr. said “There was a lot of violence, a lot of drugs. My parents didn’t have all the resources, but they were hard-working. They stressed school and being respectful. It sounds cliche, but most of the guys I came up with are now dead, in jail, or doing really bad.”

He honed his toughness playing tackle football in the streets with bigger, older kids. But basketball was his first love. The Run-N-Shoot facility was an oasis that kept him away from the temptations that his peers fell victim to.

One middle school teammate was a neighbor, a quiet kid with long arms and legs, and a sweet shooting stroke for whom basketball was also a security blanket. His name was Kevin Durant.

“I was more outspoken at that age than Kevin,” Bowman Sr. said. “He was quiet and would defer to others. But he was so skilled, so long, and could score all day long. I’d be telling him to shoot every time he touched the ball. Even at that young age he was something special.”

Bowman Sr. played for the nation’s most revered AAU team at the time — DC Assault — with other future NBA players, such as Nolan Smith and Michael Beasley.

As a junior at Suitland High School, he was among the nation’s top football recruits after compiling 165 tackles, nine sacks and three fumble recoveries on defense. On offense, he rushed for 1,200 yards and scored 22 touchdowns. After his junior season, he was named Washington Post first-team All Met, first-team all-state, and Maryland Defensive Player of the Year.

He also received basketball overtures from Clemson, Wake Forest, N.C. State and others before focusing solely on football. “I wasn’t getting any taller,” said Bowman Sr., who is 6-foot. “But hoops was always my first love.”

Notre Dame High School

Home on summer break after his freshman year at Penn State, Bowman was stuck in a traffic jam on a balmy Friday night on Okie Street in northeast D.C. Mikale was a few cars down, dressed up, out with friends, and sitting in the same congested stretch en route to Dream, a popular nightclub.

When Bowman Sr. walked over to say hello amid the spontaneous block party atmosphere that was fueled by the stalled cars’ blaring music, Mikale was taken aback by the commotion surrounding her.

“That’s NaVorro! That’s NaVorro!,” her friends yelled.

Mikale was a track athlete at Largo High School, Suitland’s rival. She was a 100-, 200- and 4×100-meter sprinter.

“I’d heard his name before and my girlfriends knew him from Suitland,” said Mikale. “I ran track but didn’t really follow sports, so I didn’t see what the big deal was. But when he came over to the car, I noticed how handsome he was, with this big, beautiful smile.”

Their first phone call was more serious than Mikale expected. The young man was vulnerable, talking about how deeply hurt and affected he’d been by the recent death of his father. That initial conversation lasted hours.

“I felt his pain on a very personal level because my father was murdered when I was 14,” said Mikale. “We’ve been stuck together like glue ever since.”

On Fridays, when Bowman was at Penn State, she’d leave work, either from the Universal Hair Salon in Fort Washington or her gig as an assistant at a Bethesda realtor’s office, and drive four hours to spend her weekends in State College, Pennsylvania.

Some of those autumn Saturday afternoons were spent among the other 106,000 spectators in Beaver Stadium as she watched her boyfriend become one of the nation’s most dominant college football players.

Two years after their first conversation, she was still taking those long weekend drives, but now with infant NaVorro Jr. strapped in his rear car seat. By then, Bowman Sr. was wrapping up a decorated college career as an All-American and two-time first-team All-Big Ten linebacker before forgoing his final year of eligibility to enter the 2010 NFL draft.

“Ever since he got cut from his first AAU team, it’s been a process. He didn’t like that feeling.”— NaVorro Bowman Sr. on his son NaVorro Bowman Jr.

By the time Bowman Jr. enrolled in middle school, he was a blur from sideline to sideline, baseline to baseline on the basketball court. His jump shot was dependable, and his handles crisp.

“He had a unique flair with the way he moved and handled the ball,” said Mikale. “He wasn’t just good, he was entertaining. And he wasn’t chasing points or hunting shots. He let the game come to him.”

Mikale had seen the brutal toll that football exacted on her husband and his peers. She was grateful that he walked away physically and mentally intact, and for the upward mobility it provided their family. But she had long told her son — in no uncertain terms — that he’d never be allowed to play the game that made his father famous.

So imagine her surprise, when picking him up from The Bullis School one early fall afternoon, to see her eighth-grade son clad in shoulder pads and gripping the face mask of a helmet that dangled by his side.

“I’d been hinting for a while about wanting to play, but she either didn’t catch on or was just ignoring me,” said Bowman Jr. “I was going to all the early training sessions and practices, telling her that I was staying late at school to study. She just stared at me with this cold look.

“My dad must have smoothed things over because I was allowed to play. And I absolutely loved it. I played running back, receiver, corner[back] and defensive end. It was the most fun I ever had. I had to get it out of my system because I knew that in high school I wanted to give everything I had to basketball.”

As a freshman at St. Paul VI in northern Virginia, Bowman expected to be a varsity contributor on a D.C. area powerhouse that is perennially ranked among the nation’s top high school basketball teams. But he’d have to wait his turn.

That 2023-24 St. Paul VI team finished as runner-up in the Chipotle Nationals, losing to future No.1 NBA draft pick Cooper Flagg’s undefeated Montverde Academy (Fla.) squad in the championship game. St. Paul VI featured five starters who earned major NCAA Division I scholarships: Ben Hammond (Virginia Tech), Garrett Sundra (Notre Dame), Isaiah Abraham (Connecticut), and Darren Harris and Patrick Ngongba (Duke).

After fall workouts and practices before the start of that season, Bowman Jr. was sent down to junior varsity.

“He didn’t like that one bit,” Mikale said. “He was upset and sulking around. I finally had to tell him, ‘Your path is your path. Stop worrying about what other people are going to say and think. Even Michael Jordan and Chris Paul played on their high school JV teams. A few years from now, nobody is going to care what you did as a freshman.’ ”

After a few weeks, Mikale noticed a shift in her son’s demeanor. He hopped in the car one afternoon after practice, smiling, and volunteered without provocation: “I actually like this now. I’m having fun.”

“Not making the varsity at Paul VI messed with me a little bit,” said Bowman Jr. “It was humbling. I was practicing against two of the best senior guards in the country every day in Ben Hammond and Darren Harris. It was a reminder that I had a lot more work to do.”

In early February 2024 during his son’s freshman year, Bowman Sr., then a defensive analyst at the University of Maryland, received a call from his former San Francisco 49ers coach, John Harbaugh. He asked Bowman Sr. to join him and the Los Angeles Chargers as their linebackers coach.

While Mikale was having lunch at a restaurant shortly after Bowman Sr., was hired by the Chargers, an acquaintance asked her about the Los Angeles-area schools they were thinking about enrolling their son upon their return to the West Coast.

“You should really look at Notre Dame,” the man advised. “I’m close with [rapper] Master P. That’s where his son went.”

Mercy Miller, the son of the rap icon and founder of the legendary hip-hop label No Limit Records, was a star basketball player at Notre Dame. In December 2023, Miller set the school’s single-game scoring record with 68 points before accepting a scholarship to the University of Houston.

“We were looking at Harvard-Westlake, Sierra Canyon and some others at that point, and the guy calls Master P and hands me his cell phone,” Mikale said. “And P was like, ‘I heard your son’s good. Y’all should go to Notre Dame.’ ”

After a number of visits, most of the coaching staffs were lukewarm at the prospect of Bowman Jr. — who’d only played junior varsity ball — joining their teams. But the Notre Dame visit was different.

“The energy from that visit felt like home,” said Bowman Jr. “The admissions director took us around, and the coaches seemed genuinely excited about having me there.”

If there were any doubts about the new sophomore from D.C., they were quickly assuaged during fall practices. Bowman turned more than a few heads with his poise, body control, playmaking, long-range shooting, and his ability to attack the rim and create his shot off the dribble.

“Right before Little NaVorro left to go to California, he’d turned the corner,” said Williams. “He grew, got better, and blew up during his sophomore year out there.”

When one of Notre Dame’s projected starters was injured during a fall league game against Redondo Beach, Bowman Jr. came off the bench and scored 21 points without missing a shot. He has started every game since.

“As soon as he got here, it was undeniable how good he was going to be offensively,” coach Sergeant said. “The initial questions we had were from a defensive and rebounding standpoint. But by late October, early November, we saw a kid with the whole package. It was obvious then that NaVorro was going to be a special player for us.”

Notre Dame High School

Playing alongside Tyran Stokes, a gifted 6-7 wing and the consensus No. 1 player in the Class of 2026, Bowman Jr. was a nationwide revelation once this season tipped off.

He averaged 16.4 points over his first nine games, including a 26-point, five-rebound, six-assist gem against Mater Dei, as Notre Dame raced to a 9-0 start to the season. During the team’s run to the state semifinals, he averaged 23 points per game.

“As soon as he started having success, those schools that weren’t really feeling him started calling,” said Mikale. “But I made it clear that we weren’t interested in hopping around. We liked where he was, and he was going to stay there.”

The momentum continued snowballing on the Nike EYBL (Elite Youth Basketball League) circuit last summer. Playing on NBA star Russell Westbrook’s Team Why Not squad, Bowman Jr. established himself as one of the nation’s most electrifying backcourt talents and California’s top-ranked point guard in the Class of 2027.

And with Stokes suddenly withdrawing from Notre Dame on Nov. 5, Bowman Jr. will be playing under a more intense spotlight this season.

“Ever since he got cut from his first AAU team, it’s been a process,” Bowman Sr. said of his son. “He didn’t like that feeling. When he started to experience success against the top guys, he never got complacent and always answered the bell.”

Bowman Jr.’s hunger hasn’t waned. Judging from chatter on the grapevine as his junior season is underway, it’s only become more ravenous.

“I follow my dad’s example and listen to everything he says, like starting my workday at 5:30 a.m. while my competition’s sleeping,” Bowman Jr. said. “He’s excelled at the highest level of sports, and he’s a coach. And he also helps me from a mental standpoint, with simple stuff like making my bed every morning to start the day off by accomplishing something.”

As the scholarship offers grow, so is that hunger that was predicted when he was 9.

“Offers don’t mean anything,” said Bowman Jr. “If anything, it’s made me want to work harder to get more. The only goal in front of me right now is for us to win a state championship. The chip on my shoulder is getting bigger, just like that first time I got cut.”

The post NaVorro Bowman Jr. is forging a separate path from his NFL dad appeared first on Andscape.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0