Black Americans’ influence on Washington, D.C., etched in design, stone and history

“I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.” — Michelle Obama. Former first lady Michelle The post Black Americans’ influence on Washington, D.C., etched in design, stone and history appeared first on TheGrio.

They left marks of Black achievement in spite of suffering and racist humiliation.

“I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.” — Michelle Obama.

Former first lady Michelle Obama uttered that now-famous line during her speech at the Democratic National Convention in 2016. And during Black History Month, it’s fitting to recognize the contributions Black Americans made in building and honoring monuments and moments in the nation’s capital.

While substantive and undeniable, the legacy of Black American influence in Washington, D.C., came with pain and suffering. The new federal city of Washington, D.C., memorials for Abraham Lincoln, and a people’s house meant to welcome all Americans remained closed to Black Americans who helped build it all. They worked for little or no wages, found solutions to difficult problems their free coworkers couldn’t solve, and suffered the indignation of segregation. Yet they persevered. These are just a few of the indelible marks of Black achievement forever etched in America’s history.

- Enslaved people helped build the White House

Enslaved people were involved in every aspect of construction, according to the White House Historical Association. From 1792 to 1800, they quarried the stone, cut bricks, and assembled the walls and roof, all the while working alongside white workers. Enslaved laborers building a symbol of hope “represents the paradoxical relationship between the institution of slavery and the ideals of freedom and liberty enshrined in America’s founding documents,” the association wrote. While workers earned wages from $0.31 to $1.34 a day, depending on their skill level, enslaved people received no pay since the enslavers took the money for themselves. This list shows the known enslaved people, at least 200, who helped build the White House and those who later worked in it.

- An enslaved man played a big role in the Statue of Freedom

The Statue of Freedom sits atop the U.S. Capitol, and the contributions of an enslaved person made it happen.

Enslaved laborers also worked on the Capitol building during its construction. One of those workers, Phillip Reid, was a self-taught foundry worker who helped produce America’s first bronze statue. The secretary of war was so impressed that he asked the foundry to produce the bronze Statue of Freedom.

The statue’s plaster cast came from Rome, but the sculptor wanted more money to separate its five sections. Reid figured out how to separate the sections to cast the statue in bronze.

Reid worked nearly every day from July 1, 1860, to May 16, 1861, and received wages of $41.25, according to the Architect of the Capitol. Even though he worked seven days a week, he only kept his Sunday pay of $1.25 daily. The rest went to his enslaver.

The Architect of the Capitol called Reid’s work “one of the most significant contributions” to constructing the Capitol.

President Abraham Lincoln freed Reid and others in Washington, D.C., on April 16, 1862, meaning Reid was a free man when the Statue of Freedom crowned the Capitol dome on Dec. 2, 1863.

- A free Black man helped survey the original boundaries of the District of Columbia

Benjamin Banneker, a free Black man from Maryland, helped survey the boundaries of the new “Federal City.” Banneker was already of some renown. He was a self-taught mathematician and astrologer, according to Biography.com. He even made a wooden clock that accurately kept time.

George Washington signed the Permanent Seat of Government Act on July 16, 1790. In 1791, the team surveying the new city hired Banneker, who worked on the project for three months before falling ill.

Still, others reveled in his success. After Thomas Jefferson, in 1785, wrote that Black people were intellectually inferior to white people, one newspaper refuted that.

The Georgetown Weekly Ledger praised Banneker, saying his “abilities as a surveyor, and an astronomer, clearly prove that Mr. Jefferson’s concluding that race of men (was) void of mental endowments, was without foundation.”

Still, when the federal government began building out Washington, D.C., they used enslaved laborers to work on a project conceived by a free Black man.

- Enslaved people raised funds for the Freedmen’s Memorial

We’re all aware of the Lincoln Memorial but might not be aware of the first Lincoln Memorial that sits one mile east of the National Mall.

The Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln was the first monument paid for entirely by the donations of formerly enslaved peoples. Dedicated in 1876, the memorial, also called the Emancipation Memorial, wasn’t without controversy since it depicts an enslaved person kneeling at Lincoln’s feet. Frederick Douglass, before an integrated crowd, gave a powerful dedication speech contrasting Lincoln’s bigotry with his desire to free enslaved people. The monument still stands today in Lincoln Park.

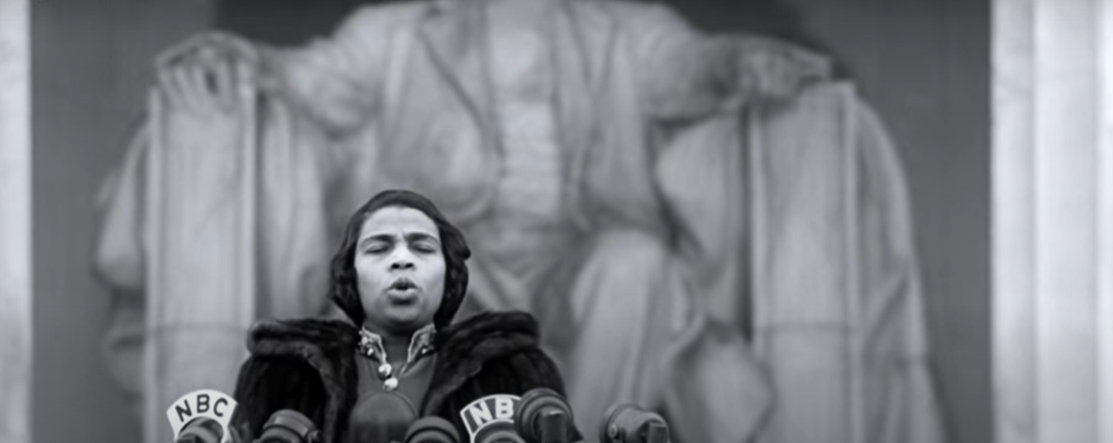

- Marian Anderson sings at the Lincoln Memorial

Marian Anderson, the most decorated singer of her time, was deemed not good enough to sing in Constitution Hall, not because of her voice but because of her skin color.

Anderson, a contralto who could sing gospel as easily as opera, spent her early years performing in Europe, where crowds were more tolerant of Black performers. The Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini, so enamored by Anderson’s talent, said her voice only comes along “once in a hundred years.”

In 1939, Howard University wanted Anderson to perform at its concert series, to be held at Constitution Hall. But the hall, owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution, wouldn’t allow her to perform in the 4,000-seat venue. First lady Eleanor Roosevelt was so appalled that she quit the DAR. Roosevelt then worked with several others, including the NAACP, to arrange Anderson’s concert at the Lincoln Memorial.

On April 9, 1939, Anderson, before 75,000 people, began her performance with “America” and became the first Black woman to sing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, a monument that stands for equality. Nearly 16 years later, she became the first Black artist to sing a leading role at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

The event’s newsreel started with, “Nation’s capital gets a lesson in tolerance.” You can listen to her performance here.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!

The post Black Americans’ influence on Washington, D.C., etched in design, stone and history appeared first on TheGrio.