Black agents are taking over the NFL representation industry

Throughout 2026, Andscape will explore the recent rise of Black agents in sports — the challenges they’ve faced in this once white-dominated industry, and how they’ve come to represent some of the biggest stars in football, basketball and beyond.

When Adisa Bakari was just a second-year law student at the University of Wisconsin, he decided he wanted to become a sports agent. The Washington native was so ambitious at the time that he even pitched to represent the top running back in school history, Ron Dayne.

Signing the 1999 Heisman Trophy winner didn’t happen. But regardless, Bakari would become a good lawyer. Fresh out of school, he landed a job in the executive compensation department at one of the country’s top media law firms.

But after four years there, Bakari felt unfulfilled in the role and decided to quit. To keep Bakari from leaving, the partners offered him the opportunity to build his own sports practice within the firm.

So in spring 2004, Bakari traveled to Alabama to recruit NFL prospects at the multiple college postseason All-Star games held there. The young lawyer’s pitch to the prospects was simple: The vast majority of professional athletes end up in dire financial straits due to inadequate representation.

After spending nearly half a decade negotiating compensation arrangements for senior-level executives on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley, Bakari concluded that athletes needed the same traditional business representation as CEOs and CFOs.

During that trip to Alabama, Bakari signed nine prospects, three of whom made NFL rosters. Over the next two decades, The Sports & Entertainment Group (TSEG), which Bakari founded with his partner, Jeff Whitney, would go on to sign All-Pro players Stefon Diggs, Le’Veon Bell, and Maurice Jones-Drew. Today, TSEG represents the most clients among Black-owned agencies (34) and is one of the most successful firms in all of football, race aside.

Yet, Bakari is constantly turned down by NFL prospects, most of whom are Black, because they’re considering bigger agencies than TSEG.

“And I’m like, ‘Yeah, we are the big agencies,” he said.

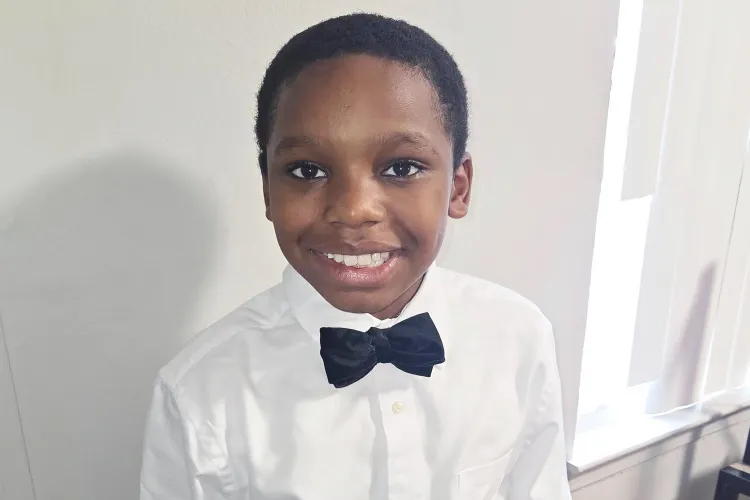

Adisa Bakari

Bakari, who is a student of African American history, understands why there is apprehension when it comes to Black representation in sports.

“I know there’s this notion of white ice is colder,” Bakari said.

So when it comes to negotiating contracts or working with majority white general managers and team owners, the assumption will always be that Black people are less capable of the job, no matter the resume they bring to the table.

White agents and agencies have dominated representation in football since the NFL’s inception in 1920. Charles “Cash and Carry” Pyle is considered the first major sports agent, representing eventual Hall of Fame running back Red Grange.

Decades later entered the original super agents: Leigh Steinberg, Drew Rosenhaus and Tom Condon. They represented most of the star quarterbacks and players of their day, such as Steve Young, Troy Aikman, Peyton Manning and Terrell Owens.

Aside from a few cases, notably a Black man from smalltown Indiana named Eugene Parker, the most powerful agents in the sport have always looked the same.

But in 2025, things have changed. Black agents and Black-owned agencies represent some of the NFL”s most high-profile players and have some of its largest rosters. David Mulugheta, president of team sports at Athletes First, negotiated more than $1 billion in contracts in 2025 and represents the second-most clients in the NFL (64) behind only Rosenhaus.

Klutch Sports Group’s Nicole Lynn was the first Black woman to represent a top-five NFL draft pick, defensive tackle Quinnen Williams, and the first to represent a quarterback, Jalen Hurts, who played in a Super Bowl.

Of the top 20 agents in the NFL based on the number of clients, four are black: Mulughetta, Lynn, Bakari and his partner, Jeff Whitney. That’s according to internal data by agency trade publication Inside the League.

But it’s not just that core. In recent years, Black agents across football have made strides that were otherwise unthinkable even two decades ago.

During the 2020 NFL draft, 17 of the 32 players selected in the first round were represented by Black agents, marking the first time that had happened in NFL history. Compare that to over a decade prior, when, from 2009-11, Black agents represented just 18 of the 96 players selected in the first round of those drafts, according to the Los Angeles Sentinel. (Seventy-six of those drafted were Black.)

Starting quarterbacks have always been the prized possession for agents, as they’re typically the highest-paid player on every team: Of the top 11 players with the highest annual salary in the league this season, all are quarterbacks.

But historically, the quarterback position has been heavily white: Just six Black quarterbacks started in Week 1 of the 2000 season, with only half of them (Donovan McNabb, Daunte Culpepper, Shaun King) having a Black agent. On the opening week of the 2025 season, there were a record-setting 16 Black starting quarterbacks, and 11 of them had either a Black agent or represented themselves.

In fact, a Black agent represents at least one of the five highest-paid players among quarterbacks, receivers, tackles, guards, centers, defensive linemen, cornerbacks and safeties, according to data from Spotrac.

“I’ve seen, much to my pleasure … an increased consciousness among Black athletes desiring Black representation and Black management,” Bakari said. “A heightened awareness of the potential for power and influence and wanting to be guided and counseled by people who share their history, share their story, [by people who] will truly understand them as people and not just see them as commodities.”

This seismic shift in Black agent representation can be traced back to one man: Parker.

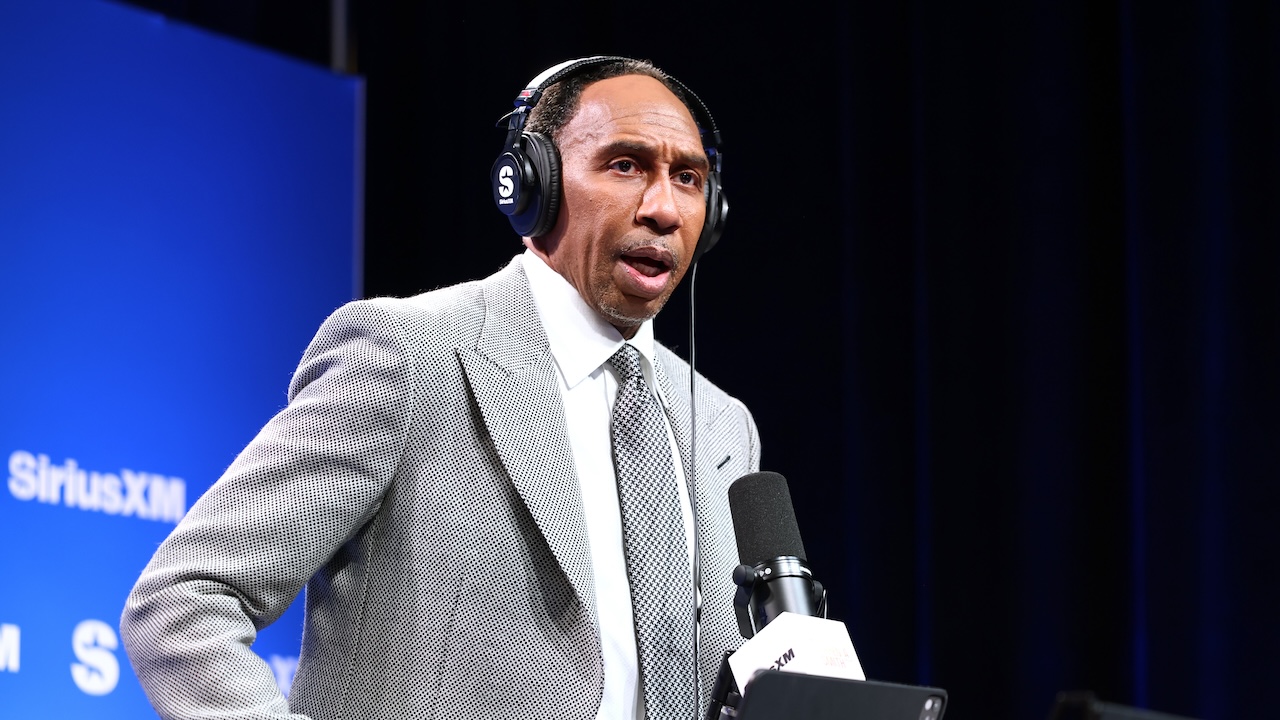

Jason Miller/Getty Images

The former Purdue basketball player, who was 60 when he died in 2016, founded Maximum Sports Management in 1993 out of Fort Wayne, Indiana, a faraway land compared to New York City or Los Angeles. Along with John Wooten — who represented seven first-round picks in the 1973 NFL draft — Parker was one of the first African American agents in football.

Parker’s first client was multisport Purdue athlete Roosevelt Barnes, who was drafted as a linebacker in the 10th round of the 1982 NFL draft by the Detroit Lions. Parker was a serious man who cared deeply for his clients and found innovative ways to maximize their value, said Jovan Barnes, Roosevelt’s son and the president of football at Divine Sports & Entertainment.

Parker helped make Emmitt Smith, Cornelius Bennett, Larry Fitzgerald and Deion Sanders the highest-paid players at their positions, the latter receiving an unprecedented $13 million signing bonus from the Dallas Cowboys that eventually led to a rule change in the collective bargaining agreement —the “Deion Rule.”

“Negotiations are give and take,” Barnes said, “but he really found ways to make sure that the contracts were player friendly.”

By 2000, Maximum Sports Management was the third-largest NFL agency, according to Kenneth L. Shropshire, Timothy Davis, and N. Jeremi Duru’s 2016 book, The Business of Sports Agents.

“This world where … less than 30 years from Black athletes even being able to play in the NFL … due to systemic racism,” said Duru, vice chair of the board of directors for the Fritz Pollard Alliance Foundation, which seeks to promote diversity in NFL hiring practices.

Parker opened the door for so many other Black agents, including Fletcher Smith (who in 2002 helped Donovan McNabb sign a record-setting $115 million contract); C. Lamont Smith (Eddie George); David Ware (Barry Sanders); W. Jerome Stanley (Keyshawn Johnson); and Bill Strickland (Daunte Culpepper).

Parker, along with Roosevelt Barnes and brothers Carl and Kevin Poston, was an example of Black excellence that future agents sought to replicate.

“Eugene was the godfather for the brothas,” said Chafie Fields, executive vice president of team sports at Wasserman.

Fields was a receiver at Penn State from 1996-99, leaving with the eighth-most receiving yards (1,437) in school history. A nagging ankle injury cut his professional career short after three years. But through those years, he remained in contact with other Penn State players, including receiver Bryant Johnson.

Johnson, the eventual 17th overall pick in the 2003 draft, didn’t fully trust the agents he was vetting and instead wanted Fields to rep him. Fields wasn’t certified at the time and agreed to be an advisor instead. Fields said he took that as a sign from above that he needed to be an agent.

“At that point I realized it was something that the Lord had decreed,” said Fields, who passed the certification exam seven months later.

He has gone on to represent Ohio State receiver Jeremiah Smith, NFL receivers JuJu Smith-Schuster and Amari Cooper, and quarterbacks Michael Vick and Geno Smith.

Fields chalks up his success in the business to remaining true to himself, keeping his word, and always telling the truth, even when the recipient doesn’t receive it well. While negotiating contracts and advocating for clients are Fields’ main responsibilities, he emphasizes to clients that football is their job, not who they are. They need to find what fulfills them in life outside of sports.

Fields grew up on the wrong side of North Philly, where the true entrepreneurs were the ones engaging in “illegal activities.” Sports were his way out, but when injuries ended his playing career, Fields realized he was never as passionate about anything in life as he was about competing. He doesn’t want the same for his clients.

“Nobody’s talking to these young men about life,” Fields said. “Everybody wants to be a part of their journey in sports. But that journey is a short ride, and when the bus stops you’ve got to get off wherever you’re at.”

The successes of Black agents like Fields and the founders of Universal Sports, Robert Brown and Kevin Connor, and others, fly in the face of the perception of Black agents. Much like Black people, these agents are often seen as inexperienced and intellectually inferior.

A Boston reporter once called the Poston brothers, who represented future Hall of Famers Ty Law and Orlando Pace, “total and complete buffoon[s]” for advocating for the highest possible contract for Pace.

“The perception used to be that we couldn’t get the job done,” said Jovan Barnes, who represents Seahawks defensive end Leonard Williams, Cowboys defensive end Dante Fowler and former Las Vegas Raiders receiver Henry Ruggs.

Barnes grew up in the business, watching his father and Parker represent some of the biggest names in football. By the time Barnes’ playing career ended in 2006, he felt he could eventually segue into the business.

“I felt like I could easily pass the [certification] test because I was learning about contracts since I was a little kid,” said Barnes, who became certified in 2013.

Over his decade working as an agent, Barnes has watched the prominence and number of Black agents increase, which he chalks up to more Black people in positions of power within the NFL. During the 2023 season, there were five Black team presidents and eight Black general managers.

A year later, there were seven Black NFL coaches to start the season. One of the excuses used for not hiring Black agents is that they would struggle to forge relationships with white coaches and front-office members.

“You see players saying, ‘There are no Black owners, so white guys can deal with other white guys better,’ ” Strickland, Culpepper’s agent, once told ESPN.

But now, not only are more Black people in positions of power in the NFL, but also in society.

“We’ve had a Black president since I played,” Barnes said.

That rise in Black agents coincides with an increase in the number of Black families who say they specifically want Black representation for their sons, said Jeff Whitney, co-founder and president of TSEG.

Before becoming a sports agent, Whitney spent years as a civil rights and employment discrimination attorney, contributing to the design of the Rooney Rule, the NFL’s diversity hiring initiative implemented in 2002.

Much like the others interviewed for this story, Whitney (and Bakari) does not shy away from who he is. At the core of TSEG is a desire to serve the Black community through the accumulation of generational wealth by Black athletes. While other Black agents might harp over the historical lack of access to white clients, TSEG isn’t all that bothered by it. Bakari and Whitney gift every new signee a copy of longtime sports journalist Bill Rhoden’s seminal 2006 book, Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete.

“We would be lying to ourselves, and we’d be lying to our players, if Blackness wasn’t central to this conversation” about diversity in athlete representation, Whitney said.

He points to the cultural reawakenings that took place both during the 2020 anti-Black racism protest movement and after the re-election of Donald Trump in 2024 as catalysts for an increased desire for Black representation. Whitney said we’re at a place of political division in America, where Black people are concluding that it makes more sense to stick together.

“The only people that are going to save us are us,” he said of that sentiment. “The only people that are truly going to help us are us.”

We’re barely 20 years removed from Black agents ringing the alarm about the difficulties they faced not in just signing white clients, but Black ones as well. There were many years when not a single quarterback in the league was represented by a Black agent, and the only “super agent” who came to mind was Rosenhaus or Steinberg, the real-life Jerry McGuire.

But now there’s Mulugheta and his Athletes First teammate Tory Dandy. There’s Whitney and Bakari, and Barnes, and Fields. The face of the NFL sports agent no longer looks the same.

“Now, when you think of sports agents, a Black sports agent pops up in these little kids’ minds,” Barnes said.

The post Black agents are taking over the NFL representation industry appeared first on Andscape.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0