State Terror Has Arrived – For White Folks

Apparently, “state terror” has finally arrived in America.

That is the claim M. Gessen writes in a recent New York Times opinion column, written amid national outrage over the killings of Renee Nicole Good and Alex Pretti by federal immigration agents during an expanded enforcement operation in Minneapolis. The piece is accompanied by an image of masked, heavily armed officers in tactical gear, rifles slung, faces covered, moving through a residential neighborhood like an occupying force.

Gessen’s catalog of violence is chilling: Renee Nicole Good, a white middle-class mother, shot and killed by ICE. A pregnant immigration lawyer threatened. U.S. citizens dragged from their homes and cars. Children tear-gassed. Airport workers rounded up and forced to show papers. A 5-year-old detained. And now Alex Pretti, a 37-year-old ICU nurse, shot to death by Border Patrol agents, reportedly while already subdued on the ground.

The article’s tone is alarming and the framing tells on itself, not because the fear is irrational, but because the fear is late. It casts state terror as something newly imported, something that has just crossed a line, something that has only now breached the boundaries of “real America.” The language rests on the assumption that this kind of force is an aberration and a deviation from the nation’s true character, rather than one of its oldest governing tools.

What is really being named is not the birth of state terror, but the moment it has slipped the leash of racial containment and bumped up against white bodies.

For Black folks, masked men with guns, arbitrary detention, children seized, bodies made disposable, and law operating as spectacle rather than protection have never been unthinkable. They have been the grammar of white supremacy in America. The only thing new is the target. The only thing unprecedented is that the terror is no longer confined to populations already marked as expendable. It is now visible in white communities, attached to white names, and narrated through white shock.

So when Gessen declares that America has crossed into something darker, what they are really documenting is a collapse of insulation. The machinery did not suddenly become fascistic; it simply widened its reach. What feels like a rupture is actually a recognition lag finally closing. This is not the arrival of state terror. It is the end of the illusion that it was ever absent and that citizenship and whiteness would provide armor from it.

Because state terror does not “arrive” in a country that built itself on slave patrols and settler militias, where policing was born as a racial project and expanded into a national creed. It does not suddenly appear in a nation that perfected surveillance, political repression, and extrajudicial killing long before this current moment. What has arrived is not terror. What has arrived is recognition, and it has arrived unevenly.

Black thinkers have been trying to hand this recognition to America for generations, and America has spent those same generations refusing to accept it.

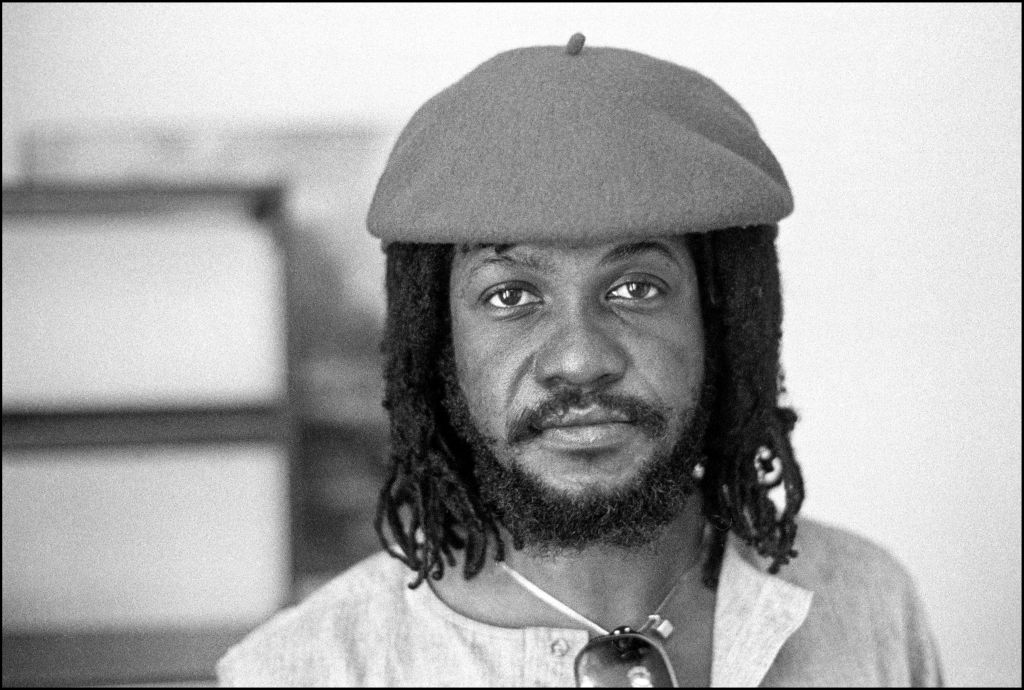

Langston Hughes said it plainly in 1936: “Fascism is a new name for the terror the Negro has always faced in America.”

That sentence wasn’t a metaphor. It was a clear-eyed diagnosis. Hughes was not claiming that America might one day become something unrecognizable. He was telling white folks that the evil they were afraid of abroad was the thing Americans have been trapped inside at home. White folks were just now learning to call it by a name that makes you tremble.

James Baldwin came along and said essentially: y’all are late, and y’all are sentimental about your lateness. Baldwin watched white America discover the vocabulary of tyranny the way a man discovers fire after spending decades lighting other people on it.

He wrote that though the word “fascism” was newly fashionable on white tongues, it “describes perfectly the conditions under which the American Negro has lived for nearly a century.” He also said that the police were the state’s muscle, “present to keep the Negro in his place and to protect white property.” Baldwin wasn’t asking whether America had become authoritarian. He was exposing how democracy was always selectively administered, and how whiteness functioned as the receipt for full citizenship.

W.E.B. Du Bois went even further back and refused the convenient lie that fascism was a European freak accident. Du Bois insisted that Europe’s racial empires were the rehearsal space where the doctrines of hierarchy, the propaganda of civilization, and the brute violence needed to enforce extraction were the parent technologies. When white people looked at Hitler and acted astonished, Du Bois was basically saying: you’re looking at colonialism coming home. You are watching Europe do to itself what it perfected doing to the world.

Paul Robeson, speaking from the belly of the mid-20th century anti-fascist struggle, refused to separate fascism from capitalism, segregation, and imperial policing. He understood Jim Crow not as a regional quirk but as an American form of dictatorship enforced by law, courts, vigilantes, and the daily threat of punishment. For Robeson, fascism was not just a set of symbols or a foreign leader; it was “a worldwide system of reaction against the liberation of mankind,” and Black people recognized it immediately because we had already been living under its domestic version.

Richard Wright understood Jim Crow as a total system of domination long before Americans were comfortable using words like totalitarian or fascist to describe themselves. In his book Black Boy and his political essays of the 1940s, he showed how Southern life functioned as an all-encompassing regime. The police, courts, schools, newspapers, churches, mobs, and economic punishment worked in concert to enforce a single racial order and crush any deviation from it.

There was no private refuge, no neutral institution, no safe interior life untouched by power. The state and the mob were not opposites but partners, and ideology and violence were fused. Long before white intellectuals warned that democracy might “slide” into authoritarianism, Wright was documenting a society in which authoritarian rule had already been perfected and racialized, made invisible by being normalized.

Wright also criticized U.S. racism in the context of fighting fascism abroad, arguing the U.S. could not oppose fascism overseas while practicing internal oppression. In a speech reported in 1941, responding to critics who said Native Son harmed the U.S. war effort, he said that those who want to “conquer the fascist enemy” but refuse to rid the U.S. of its own racist, fascist-like practices are engaging in moral evasion. For him, racial tyranny at home undermined any legitimate fight against fascism abroad.

And when Angela Davis came later and looked at policing, prisons, surveillance, and the criminalization of Black life, she made the continuity plain. She argued that the state did not suddenly become punitive. It had always been so. It had simply developed institutions sophisticated enough to make domination look like administration. What older generations experienced as lynch law, newer generations experienced as “law and order.” Same function, new paperwork. Same terror, upgraded vocabulary.

This is why the real headline of that New York Times piece should not be “State Terror Has Arrived.” It is: state terror has become legible to people who once mistook protection for innocence. The violence didn’t start when it reached white bodies. The language started when it reached white bodies. The terror became a “crisis” when it breached the racial border that kept democracy looking clean.

So the question is no longer whether the United States has “become” authoritarian, as if authoritarianism is a sudden deviation from the national story. The question is what it means that whiteness is only now naming what Black people have always lived under, named, survived, and warned about. What does it mean that Black intellectual life has been screaming the diagnosis for nearly a century, and white America is treating it like breaking news because the blood on the pavement now belongs to people it was trained to see as default citizens?

It means the country has always operated under two parallel political realities. One where democracy is assumed, and violence is imagined as exceptional. And another where the state is experienced as an occupying force, and safety is conditional.

But here’s the dangerous hinge: recognition does not automatically produce a reckoning or justice. It often produces panic, and with it, a scramble to rebuild the buffer through new laws, new categories of expendability, new technologies of containment, and new moral myths that explain why terror must once again be properly aimed. History shows that when violence threatens to become universal, the system does not dismantle itself. It re-racializes. It redraws its boundaries. Whiteness does not move from recognition to solidarity; it moves toward fortification. The shield is repaired, not removed.

Hughes named how the nation recoils not at terror itself, but at who it touches. Baldwin warned that white panic would yield repression, not repentance. Du Bois showed how empire and hierarchy would be reasserted the moment they felt threatened. Robeson insisted that anti-fascism without racial justice would become theater and leave the machinery of domination intact. Wright revealed how fear hardens into total systems, making repression feel like common sense and obedience feel like survival. And Davis later showed how crisis becomes the pretext for carceral expansion, not freedom.

So the question isn’t whether white America can finally say the word fascism without choking on it. The question is whether it will finally refuse the system now that it can no longer pretend the system was never there.

Dr. Stacey Patton is an award-winning journalist and author of “Spare The Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America” and the forthcoming “Strung Up: The Lynching of Black Children In Jim Crow America.” Read her Substack here.

SEE ALSO:

What Would MLK Say If He Saw This Hot Mess Of A Country Now?

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0