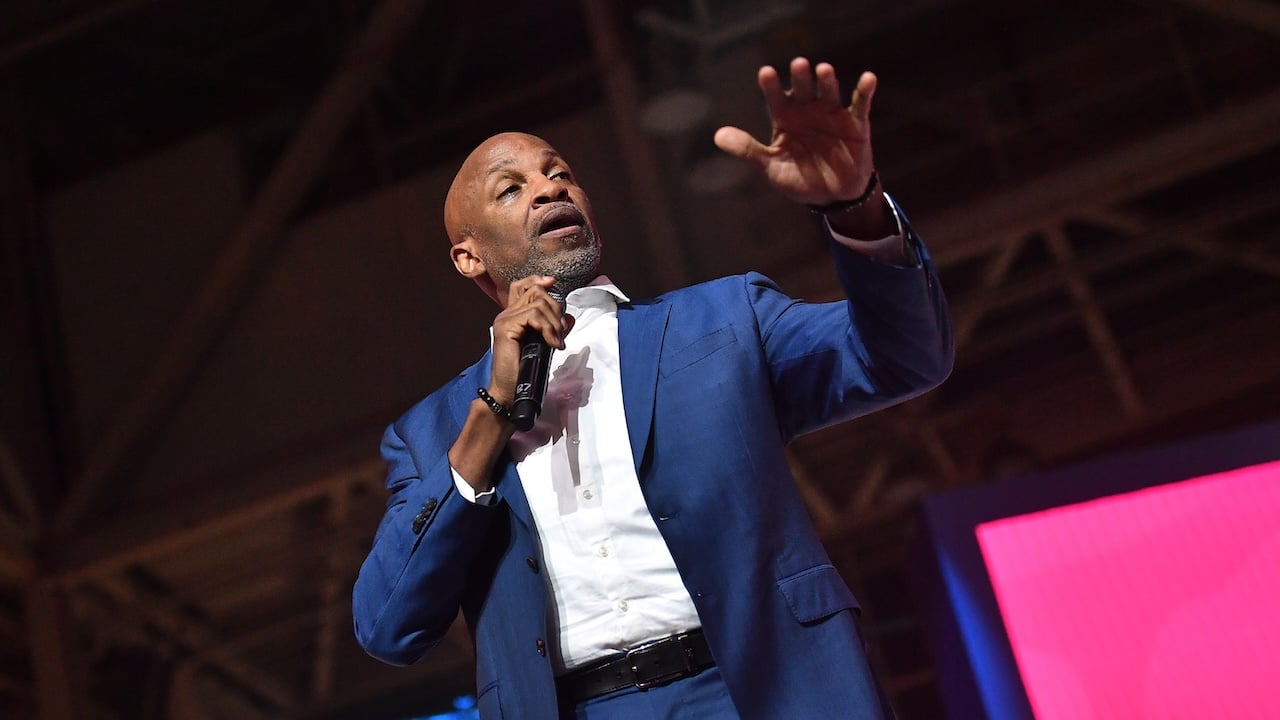

George Raveling, a leader beyond the court until his final days

On Monday, George Raveling, longtime Nike executive, and the first Black basketball coach in two of the major college conferences, died at the age of 88. Raveling broke barriers as a college player and coach, and he was a valued mentor to some of the game’s greatest figures.

In recent years, the unassuming leader re-entered the public eye, via a portrayal of him by Marlon Wayans in the movie Air, and just this August, at the Martha’s Vineyard African American Film Festival, the premiere of the documentary about his life, Unraveling George (co-produced by Charles Barkley).

Raveling was born in Washington, D.C., in 1937. His family lived above a grocery store in an apartment whose bathroom was shared by four families. His father died when George was 9, his mother was committed to a mental health institution a few years later. At 14, his grandmother sent him to a Pennsylvania boarding school, St. Michael’s. There, he earned a basketball scholarship to Villanova.

The 6-foot-6 forward averaged 12 rebounds in three varsity seasons, including 16 a game as a junior. During his senior season, when Raveling captained the team, the Wildcats played an all-white University of West Virginia team at Morgantown, West Virginia. A year before, Los Angeles Lakers rookie Elgin Baylor refused to play in a game at Charleston, West Virginia, because the three Black Lakers were denied lodging in a local hotel.

Raveling felt uncomfortable as his team’s bus approached the campus. He fouled out of the game, but afterwards Mountaineers All-American Jerry West followed Raveling toward the Villanova bench, extended his hand and said, “Good game. It was a pleasure to play against you.”

When Raveling played, only 11 Black students were enrolled at Villanova. In the 1960s, as a volunteer assistant, Raveling helped his former Villanova coach, Jack Kraft, recruit Black players Johnny Jones, Sammy Sims and Howard Porter — the latter of whom led the Wildcats to the 1971 NCAA championship game.

Nathaniel S. Butler/NBAE via Getty Images

In late August 1963, Raveling was in Delaware visiting his best friend, Warren Wilson. Wilson’s dad, a prominent dentist, asked the young men if they planned to attend the March on Washington that week. They told Dr. Wilson they had neither the funds nor the transportation to do so. He loaned them his car and handed them some cash.

The night before the march, they walked the Lincoln Memorial grounds like players checking out a basketball court prior to a game. An event marshal asked if they were interested in volunteering. He had noted their height and asked them to work security on the speakers’ stand. The next day, after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his stirring “I Have a Dream” speech, Raveling asked: “Dr. King, can I have that copy?”

When Raveling returned to Philadelphia, he placed the typed pages inside a personally signed book former President Harry S. Truman had given him when a college All-Star team visited him in his Independence, Missouri, hometown the week of an East-West game in Kansas City. Raveling never discussed the speech with anyone.

In 1969, new University of Maryland head coach Lefty Driesell hired Raveling as an assistant coach — the first Black coach in the Atlantic Coast Conference. Three years later, Washington State named him the first Black head coach in the Pac-8. After coaching future pros James Donaldson and Craig Ehlo, Raveling was hired to coach the University of Iowa in 1983.

In 1984, he assisted head coach Bobby Knight with the U.S. Olympic team. That summer, Raveling encouraged Olympian Michael Jordan, who would be entering the NBA that fall, to sign with Nike — the shoe his Iowa teams wore. Jordan was an Adidas fan who had worn Converse in college at the University of North Carolina. But Jordan held Raveling in high regard and the coach kept insisting he give the brand a try. He introduced Jordan to Nike exec Sonny Vaccaro. Jordan has said, “Without George Raveling, there is no Air Jordan.”

Raveling led Iowa to NCAA tournament appearances in 1985 and 1986, led by B.J. Armstrong, Kevin Gamble, Roy Marble and Ed Horton, after which he became head coach at USC. There he was named Kodak Coach of the Year and Basketball Weekly Coach of the Year in 1992. In September 1994, Raveling’s Jeep was blindsided in an accident that left him with nine broken ribs, a fractured pelvis, a collapsed lung, and internal bleeding. He was confined to an ICU for two weeks. During his recovery period, he resigned from USC.

From 1994 until his death, he served as Director of International Basketball for Nike. His vision helped Nike become a global brand and household name.

Nathaniel S. Butler/NBAE via Getty Images

In 2015, Raveling was inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. Three years later, he gave the Hall of Fame presentation speech for Lefty Driesell. Raveling’s college teams won 336 games, and he was voted UPI Pac-8 Coach of the Year in 1976 and 1983. His teams reached six NCAA tournaments and two NITs. He was also an assistant coach to the 1988 Olympic team.

Upon his death, Raveling’s family stated he had been battling cancer. That final adversary, and his lasting impact on players, coaches and sportswear executives, warrants a look at the leader beyond the court.

Raveling said, “You will learn that the journey of life is about discovering and rediscovering who you are. Life is about reinventing yourself and turning your wounds into wisdom. Your 86,400 seconds of unique opportunity every day must consist of you looking within and venturing closer to uncovering the plethora of your vast potential.”

And the man who turned down $3 million for his text of Dr. King’s speech stated: “The possessions you acquire will age and depreciate. Memories and serving others will last forever. Whichever field and career you pursue, understand people need to know that they matter. They need to know what they do is noticed. They need to know their efforts, whatever they might be, are not in vain.”

In two often scandalously competitive professions, Raveling earned the respect of his peers and his charges, as well as fans and media. He was in the right places in the right times, and the right mind.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0