Black Woman Principal Offers Refuge For Latino Students Living With ICE Raids

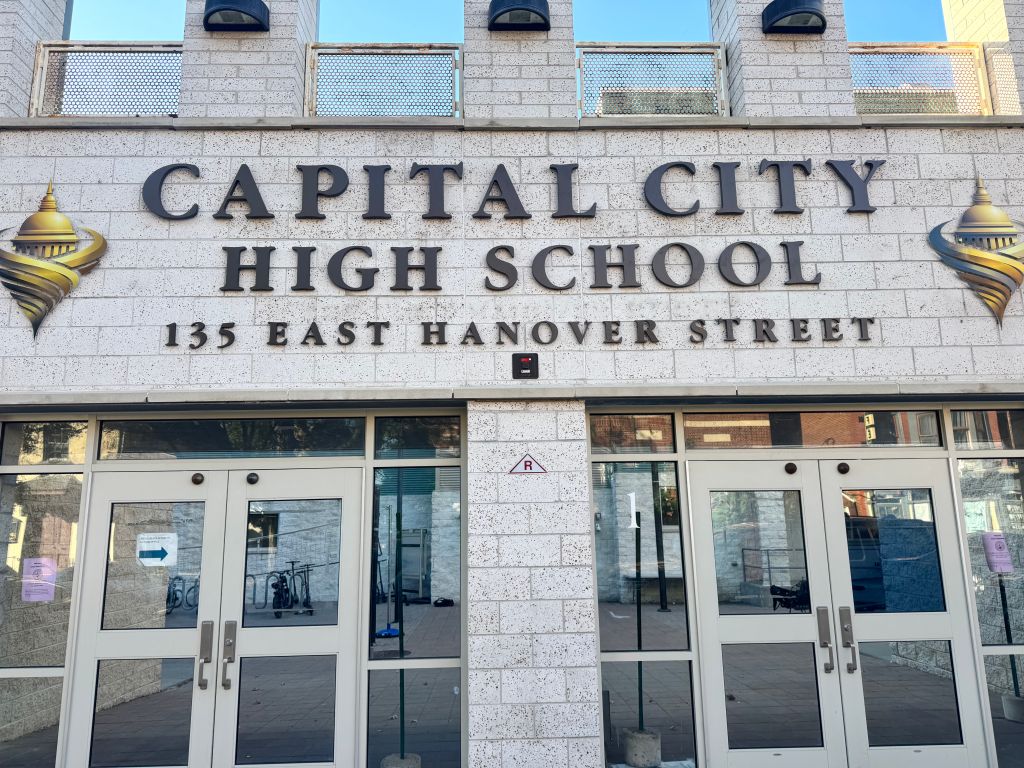

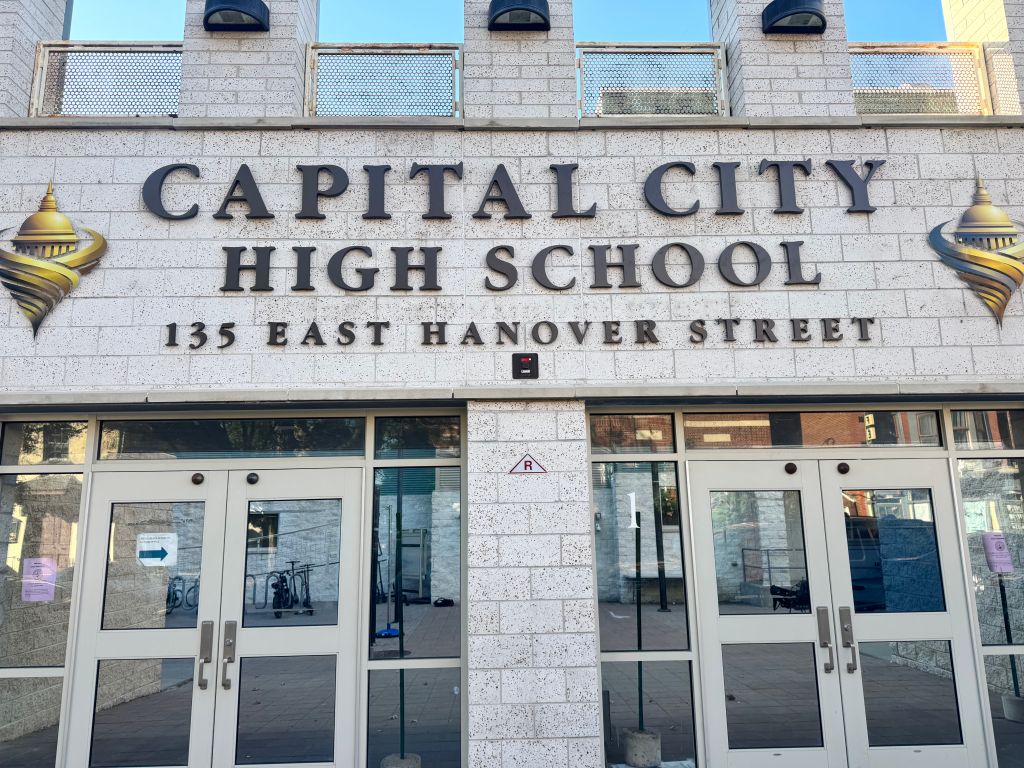

On East Hanover Street in Trenton, New Jersey, parents idle their cars at the curb as kids hustle through the front doors of Capital City High School. The white brick building sits just blocks from the State House dome, pressed up against the rhythms of downtown traffic and storefronts opening for the day. Inside, the mood shifts. Some parents clutch envelopes of paperwork, some students lower their eyes, and a nervous quiet settles over the morning rush.

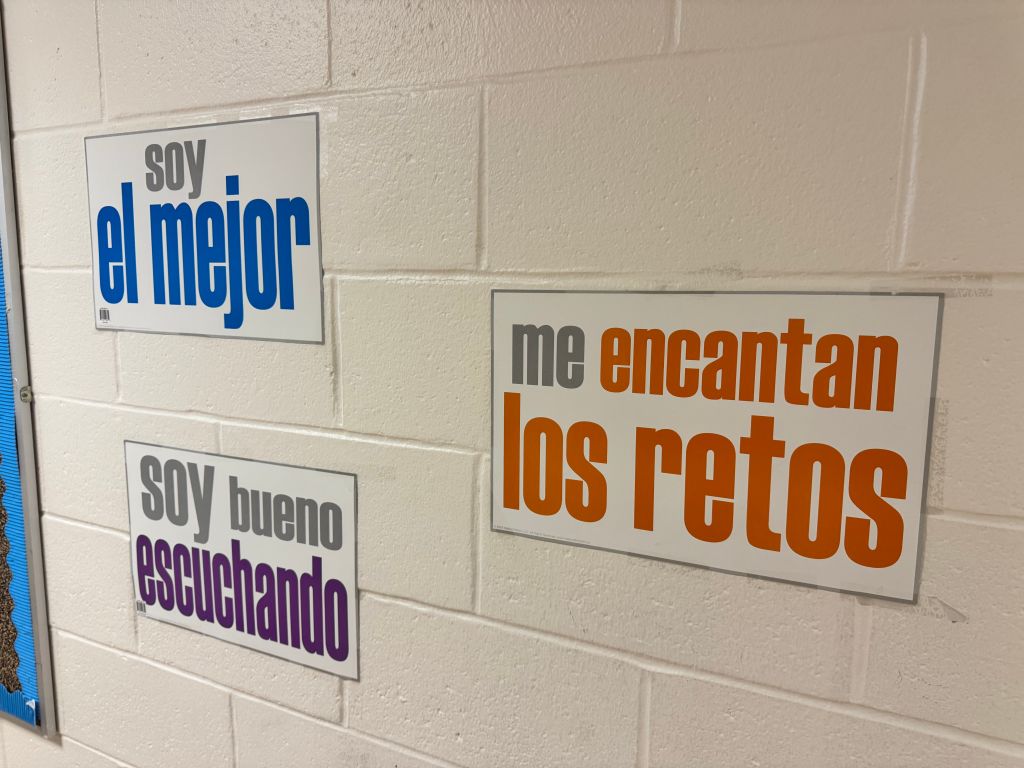

The woman standing in that doorway is Vice Principal Penny Britt. A Black administrator leading a largely Latino student body, Britt greets students with affirmations in English and Spanish. “Good morning, Beautiful. Good morning, Queen.” To those who speak Spanish, she switches seamlessly: “Hola, señor. ¿Cómo está tu día?” She tries to ease the tension that too often follows young people and their families into the building. For her, the job is as much about creating a refuge as it is about running classrooms.

That need for refuge is sharpened by the city around her. In a city just over eight square miles, Trenton’s schools are straining under budget whiplash and immigration crackdowns that spill into classrooms. At Capital City High School, 62% of the 541 students are Hispanic and 32% are Black, with only a handful of students identifying as Asian, multiracial, or white—just four students in all. Nearly two-thirds of families are navigating immigration fears on top of poverty and school underfunding.

After weeks of uncertainty, the federal freeze on roughly $158 million in New Jersey K-12 funds was lifted, but district leaders warned the damage and planning chaos were real, especially for after-school and summer programs that stabilize vulnerable students. And on the streets around East Hanover, ICE activity has rattled families. Most recently, a late-August operation drew community pushback and a response from Trenton’s mayor, deepening fears that parents won’t come home and pushing some students to stay home instead.

Inside the schools, the strain shows up in multilingual-learner metrics. At nearby Trenton Central High School, only 6.2% of English learners met expected annual growth toward proficiency last year, well below the state target, an indicator of how outside turmoil can blunt progress inside the classroom.

For Britt, those numbers aren’t abstractions. They walk through the doors every morning with anxious teenagers, parents second-guessing whether to send their children to school, and teachers juggling lessons while watching for signs of stress.

“I just want them to come in with good spirits, and to be able to leave whatever has happened prior to arriving at school at the door,” Britt says.

Britt holds an undergraduate degree in psychology and biology, along with a master’s degree in guidance counseling and school administration. Over more than four decades in K–12 and higher education, she has moved through nearly every role in the system, an experience she now draws on to steady both students and staff at Capital City.

A typical day begins in staff meetings, toggling between testing protocols, administrative calls, and hallway greetings. She keeps one eye on the agenda and another on the flow of students outside the office, stepping out to offer a quick word when she senses someone withdrawing into silence.

By lunchtime, she is in the cafeteria, trading jokes with students while giving her staff a break from monitoring. She moves from table to table, pulling earbuds out of ears, coaxing shy smiles, reminding kids that someone sees them.

In the afternoon, she is on the phone with parents, sometimes about absences, sometimes about behavior that masks deeper fears. Immigration looms in many of these conversations. It is a shadow that stretches from the schoolhouse to the living room.

And between it all, Britt circles back to her teachers, urging them to keep compassion at the center of their classrooms. She reminds them that the stress students carry isn’t always visible, but it is always present.

Outside the classroom, the weight of immigration enforcement presses hardest on families. Parents describe the quiet dread of putting their children on the bus each morning, unsure who will be home that evening. One mother said she worries less about homework than whether she will see her son’s face after school. Another father admitted he parks his car farther from campus, afraid of drawing unwanted attention.

For students, the anxiety is no less consuming. Because of safety concerns, their names are not used in this story, and identifying details are withheld.

The anxiety is visible before a word is spoken. Walking through the school, the blank stares can be felt. Heads are lowered, eyes darting, conversations cut short out of fear of saying the wrong thing. The uncertainty that trails the recent ICE raids has seeped into classrooms and cafeterias.

At lunch, a boy sat alone with his hood pulled tight, earbuds in, fingers tapping the table in a restless rhythm. His gaze stayed fixed downward, as if he were locked in thoughts he couldn’t escape. The small movements, the fidgeting, the eyes that never settled, said more than words ever could.

This is the new reality for many high schoolers here. They do not know what they will encounter when they walk into school, or whether their families will still be intact when they return home. “We’re just trying to get through,” one student said when asked how they were coping with school in the middle of new immigration policies.

“To see people going through that and being torn apart from their families is really sad, and I don’t wish that on anybody,” another explained.

Others described how the uncertainty reshaped their sense of self. “I believe the only thing to do is to move forward,” one student reflected, trying to frame survival as resilience under Trump-era immigration crackdowns. Another admitted, “I have myself because nobody is going to have your back like you do,” a lonely calculation of how to navigate fear without leaning on adults or institutions.

And for some, the raids have sharpened their view of the country itself. “Honestly, there is no Make America Great Again because America was really never great,” a 10th grader said, connecting their personal fear to a broader disillusionment with the government.

Staff at the school see the same fear written across their students’ faces. Aricia McCathern, the Climate and Culture Specialist at Capital City, said the raids rippled immediately through attendance. “Initially, with the ICE raids, we had a decline in attendance. Students were scared to come to school,” she explained. Some of the kids who were U.S. citizens worried that their presence at school could put their undocumented parents at risk. “We even had students who questioned if they should walk at graduation because they felt ICE would be outside waiting for them.”

If Britt is the steady presence in the doorway, secretary Yadira Melendez is the first face students see inside. A native of Puerto Rico, she welcomes parents and students in Spanish, showing newcomers where to go and offering the kind of comfort only someone who understands their world can give.

“For families who are new to the country, everything is different,” Melendez said. “When they walk in and see someone who speaks Spanish, they feel more comfortable. I show them around, answer their questions, and try to give them some peace.”

Every day, she sees two or three students come to her in distress. Sometimes it’s about immigration fears, but more often it’s family struggles that weigh on them. They worry about debt, absent parents, or making money to help relatives back home who depend on them. “They have to adapt to a whole new culture, and they carry so much,” she said. “Sometimes they just need somebody to listen to. To me, they’re my babies. I treat them like my own.”

The issues can be heavy. Lately, the big issues are letters arriving from immigration courts and students worrying about upcoming hearings for their parents. They want to know what to expect, what will happen if their families are split apart. “Their concerns have spiked,” Melendez said. “They’re more willing to come and talk now because they’re looking for someone who will hear them.”

She tries to offer honesty and reassurance at once. “We tell them the reality,” she explained. “But we also tell them how to prevent problems. We tell them to stay out of trouble, don’t hang with the wrong folks, do the right thing in this community so they’re not at risk.”

When families lose a parent to ICE detention, the consequences are immediate. “To be honest, when a parent gets picked up, the kids often stop coming to school,” Melendez said. “We do home visits, and the truancy officers do wellness checks. But a lot of times, if someone in their family is taken, they either disappear from school or the family decides to return to their home country.”

Even then, she continues to link students to counseling, food pantries, and clothing drives, knowing that many of the households that take them in don’t have enough resources themselves. “At times it’s a lot,” she admitted. “But I just want to do it from my heart. I love these kids.”

Britt spends much of her time tracking down the students who don’t show up. Through the school’s CARES program, staff create what she calls a “frequent flyer list” of students with chronic absences. “We started looking at why students aren’t coming to school,” Britt explained. “What services can we provide? Who do we need to call? So we make a hot list, and then we start contacting families to figure out, you know, what’s going on with Johnny? Why isn’t he here today?”

But even when students do make it to school, staying can be a challenge. “Some of them skip because they’ve got to work,” she said. “That bothers me. When I was coming up, I didn’t have to leave school to earn money. School was the most important thing. From a cultural perspective, that’s troubling for me.”

Basic needs weigh on her just as heavily. “I worry about whether they’ve had enough to eat,” Britt said. “Yes, we have free lunch for all students, but if they come in late, they miss it. Sometimes kids want to take food home because there’s no food there.. Those things preoccupy me.” She has responded by setting up food and clothing pantries in the school, stocked through partnerships with local churches and community groups. “If a student comes in without a coat or with shoes that are too small, we take care of that,” she said. “I take pride in being able to close the divide when students don’t have access.”

Safety is another constant concern. “We’re one of the safest high schools in the district — last year we had maybe three or four fights,” Britt said. “But we still have to be vigilant. We monitor bathrooms, hallways, anywhere conflict might flare.” She credits the school’s climate and culture staff, who are trained in restorative practices, for helping students resolve conflicts before they escalate. “We bring kids together and ask, ‘What do you need from him to move through the day? What do you need from her?’ It’s about teaching them they can coexist in this building without bringing outside problems into school.”

Immigration pressures often shape those outside problems. “It’s not unusual for a student to say, ‘I’ve got to go with my mom to court because she doesn’t speak English,’” Britt explained. “Or, ‘I need to check on my sister because my mom’s sick and we live alone.’ Attendance gets hit because kids are serving as translators, advocates, even caretakers.”

What’s happening at Capital City is not unique. Across the country, schools have become frontline safe havens for immigrant families, often filling gaps left by strained public systems and hostile federal policy. For administrators like Britt, the role stretches far beyond academics. It means being a counselor, advocate, translator, and protector all at once.

When asked what she wishes policymakers understood, Britt didn’t hesitate. “Don’t put a high school in a place where the crime rate is so high,” she said. “Give us enhanced security for our students. And understand that when kids are carrying all these burdens, we need more resources to keep them safe and supported.”

What makes this story especially resonant is who stands at the center of it. A Black woman administrator providing refuge for Latino students reveals how deeply intertwined the fates of marginalized communities are. Britt brings her own lived experience of navigating racism into a role where she now shields children caught in the machinery of immigration enforcement. Her work shows how the fight for safety and dignity in education never falls neatly along one line of identity — Black and Latino struggles are braided together by overlapping systems of exclusion.

In Trenton, citizenship is tested in the most ordinary of places: at a school door, in a cafeteria, in whether a child feels safe enough to sit down and learn. Britt’s presence at Capital City High School shows how belonging is not only about legal papers but about community care and about whether schools will act as sanctuaries rather than extensions of state surveillance.

Her leadership underscores a larger truth: when one group’s children are unsafe, the whole community is diminished. And when one leader holds the line, as Britt does each morning in that doorway, she is holding it for everyone.

As the day winds down, she is still moving through the halls, checking on staff, making final calls, walking one more family out the door. For Britt, success isn’t measured in test scores or graduation rates, but in whether students feel safe enough to walk back through those doors tomorrow.

Amyah Wright is a Howard University journalism student and campus leader passionate about media, mentorship, and community impact. She aims to use her platform in broadcast journalism to amplify diverse voices and tell stories that make a difference.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0