A’ja Wilson is the WNBA’s — and her parents’ — dream come true

PHOENIX — Prior to Game 3 of the WNBA Finals, Eva and Roscoe Wilson indulged me for a trip down memory lane.

We went back to Oct. 24, 1996. I was a reporter in New York assigned to cover an event announcing a new women’s professional basketball league: the WNBA.

On hand at the event were two high-profile players from the women’s national team that had just won a gold medal at the 1996 Olympics: Sheryl Swoopes and Rebecca Lobo. They were ecstatic about the formation of the new, NBA-sponsored pro league for women.

“I can’t tell you how happy I am to be able to play professional basketball in the United States,” Swoopes said.

Lobo, the national player of the year two years earlier at UConn, said she was happy, not only for what the WNBA meant for current players but for what the new league would mean for future generations of young girls.

“A lot of little girls are smiling, knowing they have a chance to dream and that dreams can come true.” she said.

New York Times

About 700 miles away in Columbia, South Carolina, the Wilsons, who were married in 1992, were adjusting to life with their 3-month-old baby girl.

Her name was A’ja and she was the light of their lives.

Twenty-nine years later, A’ja Wilson, a 6-foot-4 center, is the embodiment of the dream Lobo referenced in 1996. She is the face of the WNBA and arguably the most dominant player in league history. Wilson has won a collegiate national championship, two Olympic gold medals, four WNBA Most Valuable Player awards and a pair of WNBA titles with the Las Vegas Aces.

On Wednesday, Wilson’s game-winning shot with less than a second left put the Aces on the brink of winning their third title in four years.

Of course, in October 1996 none of this was on the Wilson’s family radar screen.

David Becker/NBAE via Getty Images

In 1996, Eva was a first-time mom and Roscoe, who had a son by a previous marriage, was celebrating having a girl.

“From my side of the family, A’ja was the first girl out there,” Roscoe said in an interview before Game 3. “We had all boys. so that just blew me away. The fact that I got a daughter, I started wearing pink. I was just going crazy, but I was glad to have a daughter.

“I was just looking forward to being as good a parent — or trying to be as good a parent to my daughter and my son — as my father and mother were for me. That’s what I was looking forward to: I’m going to be trying to be the best dad I can be.”

Eva was enjoying motherhood.

“I was very excited. She was my first and I pretty much was thinking she was going to be my only,” she said. “I wasn’t sure, but in my mind I’m saying, ‘This is it.’ But it was just excitement and just the anticipation of motherhood for me. The anticipation of just walking into motherhood for the very first time.”

For the first eight or nine years of A’ja’s life, her parents involved her in every imaginable activity.

“We had her doing all kinds of different things,” Eva recalled. “She did ballet, she did tap, she did gymnastics, she played soccer, she did tennis, did karate, she did piano. She did the whole nine; she did the whole stretch.

“But as far as thinking that she would be an athlete, I didn’t know enough about it to claim that one way or another. I left that totally with Roscoe. I was on the opposite side with the arts and the education. He was the sports part.”

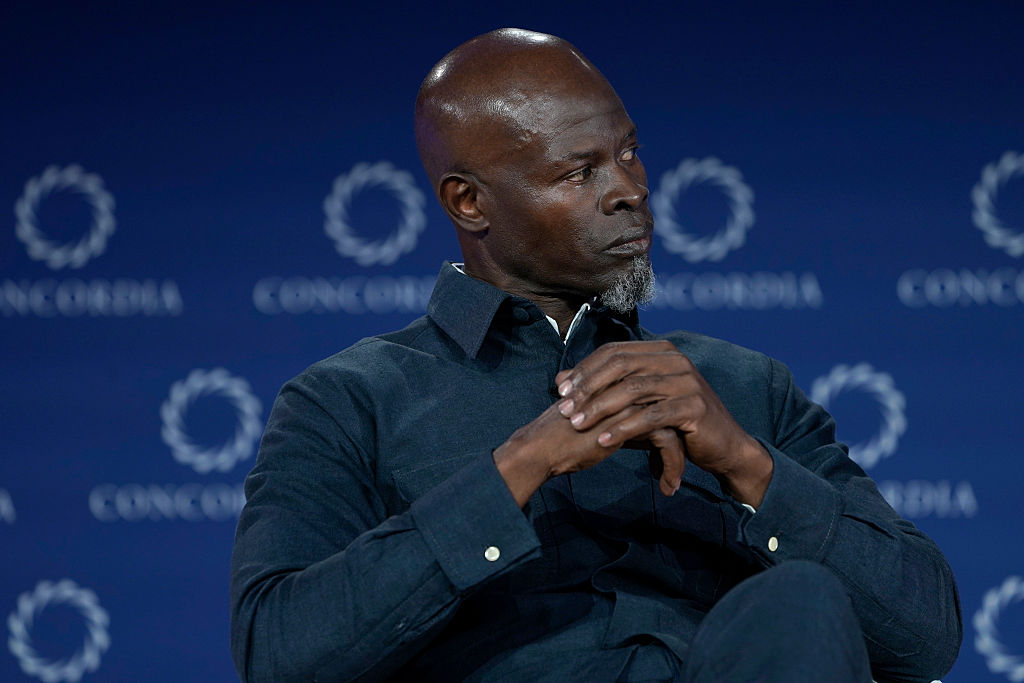

Wilson played college basketball at Benedict College, a historically Black college in Columbia, South Carolina. He went on to play professional basketball in Europe and South America for 10 seasons. By October 1996, Wilson, then 44, had been retired from playing for eight years. He coached men’s and women’s basketball, track and field, softball, and also served as athletic director at Morris College in Sumter, South Carolina.

He was an early fan of the women’s game.

“I watched the game, not so much that my daughter would play,” he said. “I watched it just because I like basketball. When I played in Europe, women’s basketball was a big deal. I coached one of the best teams in Sweden, so my appreciation for the game goes way back, before 1996.”

Christian Petersen/Getty Images

A’ja was not a willing protégé. Of all the activities she was exposed to, basketball was the last sport she picked up. Roscoe wasn’t stuck on A’ja being a hooper, but he did want her to be an athlete.

“Basketball was almost a last thing that we even tried with her, because she liked soccer and she liked volleyball,” Roscoe recalled. “Athletes are more well-rounded and they see various aspects of life and they can draw things for life from sports. So, I just wanted her to do that.”

Ultimately, A’ja began having so many growth spurts that Roscoe decided to nudge his 10-year-old daughter toward basketball. By then, the WNBA was in its 10th year of operation. Women’s basketball was flourishing; the time was right. Wilson and a friend started an AAU team just so their daughters could play. Neither one was very good, but A’ja, perhaps because she was an only child, enjoyed the team environment.

“She wasn’t very good, but she was just happy to be on the team, giving out water, cheerleading,” Eva said. “She just liked being on the team.”

In time, A’ja developed an affinity for the game, then a passion and, finally, a love. Roscoe can’t pinpoint the exact moment, though he remembers one particular moment.

“She had a real good game. We put her in when it was like 44 seconds to go. She went in and she had, like, three or four 3s. I’m like, ‘Whoa.’ So, she started liking the game. I said, ‘A’ja, if you want to play this game, you’ve got to commit to being better.’ And that’s where it started. I said, ‘If you commit, I’m going to commit.’ So, I shut everything down. All I did was train A’ja.”

The rest, as they say, is history. A’ja was on the star trajectory, though Eva Wilson was adamant that her daughter would have a balanced middle school and high school experience.

“I was the education part,” Eva said. “I made sure that the grades were straight, everything’s prepared for academic success, and also making sure that she was involved in other things other than basketball, whether that be ballet or Girl Scouts. She went all the way up to cadet in Girl Scouts. I made sure she had that side.”

Roscoe took care of basketball and self-confidence.

“I knew she was going to be something,” Roscoe said. “I mean, everybody thinks their child is special. But it didn’t hit me until A’ja started to grow in AAU and grow in high school and college. I told her, ‘A’ja, you have to train yourself and get in the frame of mind that when your coach looks down and sees you sitting on the bench, that coach needs to say, ‘Why the hell ain’t I got age A’ja in the game?’ ”

Today, Eva and Roscoe’s daughter is the epitome of balance. She has written an autobiography, “Dear Black Girls: How to be True to You,” developed the A’ja Wilson Foundation, and is on the brink of winning her third WNBA title.

During that event in October 1996, a league official predicted that it would take a generation for the WNBA to truly hit its stride.

Twenty-nine years later, Wilson is the league’s dream come true.

The post A’ja Wilson is the WNBA’s — and her parents’ — dream come true appeared first on Andscape.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0